How did my listening evolve? Spotify Wrapped 2024

It’s time for my annual deep dive into Spotify Wrapped! I continue to primarily listen to music I own and diversify my streaming habits beyond Spotify to include SoundCloud and YouTube as well. As a result, my Spotify Wrapped is less and less representative of my actual listening history.

Let’s dig into my top artists and tracks of 2024 according to each service, and dive into the Spotify Music Evolution categories.

You can use this table of contents to skip around:

Comparing Spotify with SoundCloud and Last.fm #

I’ve been using Last.fm to track what I listen to since 2007. In this post I’ll compare the insights that I got this year from Spotify Wrapped and SoundCloud Playback with my Last.fm data. These data sources are not equivalent.

My Last.fm data is accurate to within minutes, so might even change as I’m writing this post, and tracks most of what I listen to, no matter what I used to listen to it (with some limits).

SoundCloud has a help article, Your Playback playlists, that doesn’t list a time range for 2024 as I’m writing this, but lists the time period covered by SoundCloud Playback in 2023 as from January 1 – November 30 for 2023 and earlier, so I’ll comfortably assume that the 2024 version covers the same time period. The Playback, of course, covers only what I listen to on SoundCloud.

For the first time ever, Spotify Wrapped, according to the Spotify Wrapped article on their support site, uses data from November. They’re very vague about it, however:

The 2024 Wrapped personalized experience covers the music and podcasts you streamed from January 1st, 2024, to a few weeks prior to launch on December 4th, 2024.

I’d guess that the cutoff is around November 15th, informed by my own data and an uncited Wikipedia edit that I spotted while researching this. To make this happen, some engineers at Spotify probably improved their data processing infrastructure, or they reduced the overall insights delivered in order to capture a longer time range. Either way, Spotify Wrapped only includes data from Spotify.

With those caveats, let’s do some rough analysis.

Dig deeper into your own Spotify Wrapped #

If you’re reading this and wish you had something like Last.fm to dig into your own music listening habits (and you also listen mostly to music on Spotify) then you’re in luck.

Thanks to privacy laws and regulations like General Data Protection Regulation and the California Consumer Privacy Act , you can request a download of your streaming history from Spotify. According to the site, the privacy request takes at least 5 days (for the past 1 year of streaming history) or up to 30 days (for all time listening history) to return.

Ordinarily, that data would be kind of annoying to process (unless you, like me, work for a data analysis software company, or less like me, are extremely good with spreadsheets), but Former Spotify data alchemist (hired on as part of the Echo Nest acquisition), he was one of the 1500+ people laid off by Spotify in layoffs announced last December (more on those later in this post). built a tool called Curio to help you make your own Spotify Wrapped. Announcing it in a post titled Know Yourself (For Free), he says:

It’s that time of year when companies begin pretending that a) the year is already over, and b) you should be grateful to them for giving you a tiny yearly glimpse of your own data.

But your data is yours. You shouldn’t have to elaborately ask for it, but that tends to be the state at the moment. You can get your streaming history from Spotify by going to Account > Security and privacy > Account privacy (of course).

But if you do, because you can, and you get a Spotify API key, which you can, then you can play with Curio, my experimental app for organizing music curiosity. Curio does a potentially puzzling assortment of things that I like to do, but it also has a query language, so that neither of us is limited by what I already think I want.

I’ve requested my data and I’m looking forward to exploring the lenses that Curio might enable me to see, as well as to possibly disaggregate my listening data by service.

By the way, Also the grocery store chain that I shop at, in case you also want to perform year-over-year grocery cost savings analyses (stay tuned for a future blog post I hope). provide this ability too. Look for phrases like “privacy request” or “request to know” for details.

My top artists of 2024 #

I didn’t have strong expectations about my top 5 artists on Spotify this year because I’ve been trying to use it less and less over the past few years. I did have some guesses, though.

When you evaluate music data based on frequency, what you also reveal is different patterns of how you “use” music in your day-to-day life. My partner listens to a lot of music while exercising. One friend of mine often texts me for recommendations for tracks to add to his bike playlist. Another friend plays music for her dogs.

I focus better with music and end up in a good number of “listening ruts” (see last year’s post on Bombay Bicycle Club) as a result, my listening patterns reflect various writing projects that I’m doing at work or at home (like this one!).

What were my top artists, according to each service?

| Spotify | SoundCloud | Last.fm |

|---|---|---|

| Beyoncé | SWIM | TC4 |

| U2 | Jasper Tygner | SWIM |

| Charli XCX | Overmono | Beyoncé |

| Caribou | Fred again.. | DJ Heartstring |

| Tourist | 17 Steps | U2 |

There’s definitely some surprises here, and some embarrassing admissions.

What is streaming for? #

Beyond the different functions that music serves in my life, I also use different music streaming platforms for different purposes. My top artists list reflects this.

If I’m listening to music on a streaming service it’s because I want to listen to something I don’t own, or that I’m not using one of my personal devices.

Spotify is where I go to evaluate a new album by an artist, especially if it’s being talked about a lot (Beyoncé and Charli XCX) and where I go to listen to music that I don’t own but is more classic (U2). I also do still listen to music that I own, but mostly as focus listening (Caribou and Tourist).

On SoundCloud, I primarily listen to DJ sets, scout out IDs and remixes, and discover new artists and tracks. One artist from my top 5, 17 Steps, is actually a record label. I’m guessing that because of There are many more freeform fields—artists and labels and radio stations all have profiles, and the track name titles are derived from the uploaded name of the track, which doesn’t always match the actual official track metadata. This also makes it easier to upload and manage DJ sets and bootleg cuts and remixes, making SoundCloud a popular choice for electronic producers (and more) , it’s showing up as one of my top artists.

As far as I can tell, I’ve only liked one track from them and that track is one I’ve only listened to once, on May 11 of this year.

I might have listened to more tracks, but there’s no easy way for me to trace that lineage from my Last.fm data.

Either way, including that record label as a top artist is an odd choice, especially given that O’Flynn, Club Angel, and others show up in my top tracks in the Playback 2024 playlist (and I definitely spent at least one entire day only listening to most of the track son Club Angel’s profile on SoundCloud).

An unexpected surprise #

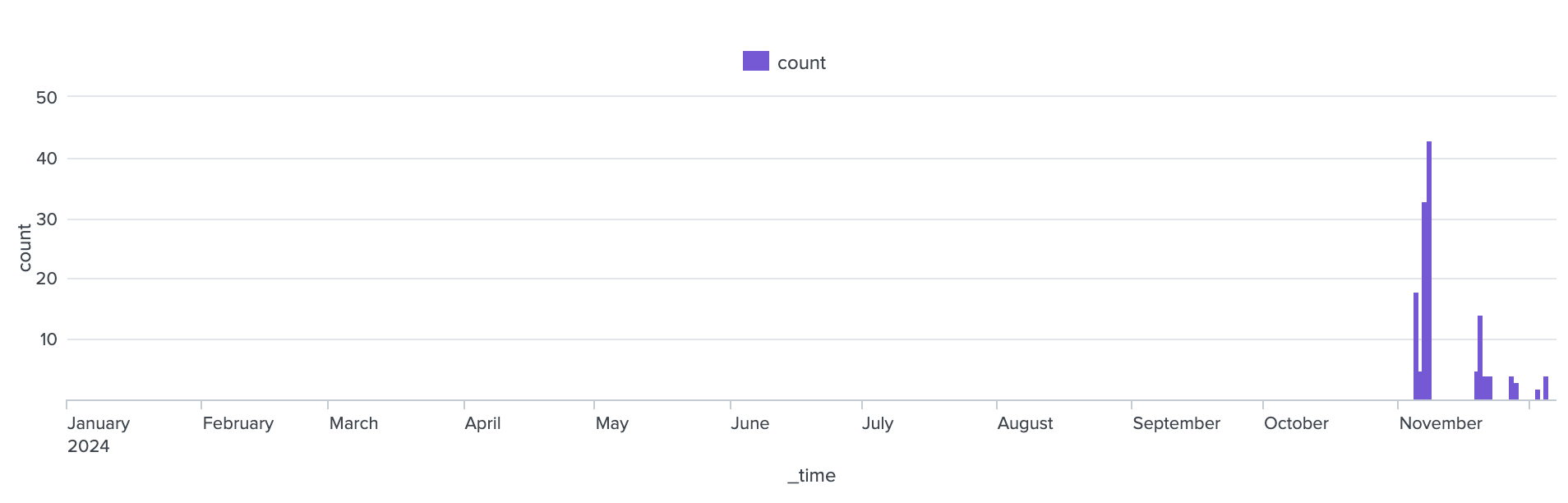

I knew as soon as I saw my top artists in this year’s Wrapped that it had extended into November, because U2 was there in second place. I didn’t listen to U2 at all this year, and then after both a conversation where I’d convinced a friend (correctly) that The Joshua Tree was an excellent album and a few impressive appearances by U2 in the documentary Eno, I simply needed to listen to them:

And then something clicked in my brain and U2 was the only thing I wanted to listen to. No really:

I don’t want to shatter any illusions that you might have had about my music taste, but soaring anthemic music exists across genres, and The Joshua Tree is excellent.

What (and who) is missing? #

There are some patterns that I expected to see in the data that are missing. Another purpose that I used Spotify for this year was digging deeper into the music mentioned in two music history books that I read:

- The Number Ones by Tom Breihan, which explores the history of evolving taste through the lens of chart topping singles from 1958 to the present.

- Let’s Do It: The Birth of Pop Music: A History by Bob Stanley, which covers the birth of pop music up until about the early 1960s.

As I was reading those books, I of course wanted to seek out the songs mentioned, and I was lucky enough to find a set of public playlists with nearly every track mentioned in “Let’s Do It” (there’s also one for the Number Ones, but it only covers the highlighted tracks, not every one referenced). In this way, Spotify served briefly as a music history experience for me — but none of that listening history appeared in my Spotify Wrapped or in my top 100 tracks, or in my “Music Evolution” playlist.

Another artist completely missing from my Spotify top artists is TC4. The artists in my SoundCloud and Last.fm top 5 artists of the year show up at least in my Top Songs of 2024 playlist, but TC4 is totally absent.

That’s because TC4 is pretty absent from streaming services as well. Their profile on Spotify is pretty empty, with only 26 tracks across 20 albums (singles) in their discography.

Meanwhile, on Bandcamp, it’s a different story. They have 93 releases, and while most of them are still 1 or 2-track singles, that’s more than triple the number of tracks available on Spotify. They also sell their discography at a discount, so I bought it in May of this year.

Even if I hadn’t fallen in love with a few of their tracks (Joy dub, Hurt you, Bandido), the sheer number of tracks in my library means that listening idly on shuffle often brings up one of their tracks.

What makes a top artist? #

Another aspect of these top 5 rankings is assessing what “top” means in the context of these rankings. You can rank artists by volume of listens, but you can also weight volume with other factors, like popularity or consistency.

I am not a machine learning practitioner and I have never taken a stats class, but I do have lots of data, so let’s do an experiment!

Are my top artists according to each service ranked only by volume of listens?

| Spotify | SoundCloud |

|---|---|

| Beyoncé | SWIM |

| U2 | Jasper Tygner |

| Charli XCX | Overmono |

| Caribou | Fred again.. |

| Tourist | 17 Steps |

The Spotify top songs playlist is ranked from most frequent to least frequent listens, so I considered that maybe the top artists would be reflected in it as well. The first five unique artists to appear in my top songs playlists from each service are the following:

| Spotify | SoundCloud |

|---|---|

| Jamie xx | SWIM |

| Caribou | O’Flynn |

| U2 | DJ Heartstring |

| Beyoncé | Bubble Love |

| Effy | Club Angel |

I’ve bolded the top 5 artists from Spotify and italicized the top artists from SoundCloud that show up in this list.

There’s some overlap, but the order is different, which makes sense. Tourist and Charli XCX have been supplanted by Jamie xx and Effy for Spotify, and it’s a totally different list for SoundCloud aside from SWIM.

So definitely my top 5 artists are not just the first five unique artists who made my top songs of the year. What about the artists that occur most frequently in the top songs of the year playlist?

| Spotify | Playlist frequency | SoundCloud | Playlist frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beyoncé | 12/100 | SWIM | 4/50 |

| Tourist | 10/100 | Overmono | 4/50 |

| U2 | 6/100 | Jasper Tygner | 3/50 |

| Bicep | 5/100 | Cameo Blush | 2/50 |

| Charli XCX | 5/100 | Club Angel | 2/50 |

| DJ Heartstring | 5/100 | DJ Heartstring | 2/50 |

| Jamie xx | 5/100 | HAAi | 2/50 |

| SWIM | 4/100 | Leon Vynehall | 2/50 |

| Caribou | 4/100 | O’Flynn | 2/50 |

| Bombay Bicycle Club | 2/100 | Ross from Friends | 2/50 |

| Chappell Roan | 2/100 | Totally Enormous Extinct Dinosaurs | 2/50 |

| Jeremy Loops | 2/100 | - | - |

| Malugi | 2/100 | - | - |

| Narciss | 2/100 | - | - |

| Tinashe | 2/100 | - | - |

The Spotify list is pretty similar to my top 5 artists, but is again in a different order and lists Bicep instead of Caribou.

If I try to backsolve for the qualities of a “top artist” according to Spotify (I won’t even try for SoundCloud, because of their mysterious metadata), I’ll start from the same presumed base: listen frequency, or volume.

These are my top 20 artists of the year by listens, according to Last.fm:

| artist | listens |

|---|---|

| TC4 | 212 |

| SWIM | 163 |

| Beyoncé | 146 |

| DJ Heartstring | 141 |

| U2 | 139 |

| Tourist | 137 |

| Caribou | 107 |

| Bicep | 106 |

| Chappell Roan | 91 |

| Jamie xx | 87 |

| Charli XCX | 82 |

| Fleetwood Mac | 81 |

| Mall Grab | 80 |

| Jasper Tygner | 74 |

| Bombay Bicycle Club | 73 |

| NOTION | 67 |

| Barry Can’t Swim | 63 |

| salute | 62 |

| Tom VR | 55 |

| Fred again.. | 54 |

To compare alternate versions of “top”, let’s also look at the total number of days in 2024 that I listened to these same artists:

| artist | days |

|---|---|

| SWIM | 66 |

| TC4 | 62 |

| DJ Heartstring | 57 |

| NOTION | 45 |

| Barry Can’t Swim | 41 |

| Tourist | 40 |

| Tom VR | 39 |

| Jasper Tygner | 37 |

| Bicep | 36 |

| Caribou | 35 |

| Charli XCX | 35 |

| Jamie xx | 34 |

| Mall Grab | 31 |

| salute | 29 |

| Fred again.. | 27 |

| Chappell Roan | 24 |

| Bombay Bicycle Club | 23 |

| Beyoncé | 17 |

| U2 | 12 |

| Fleetwood Mac | 11 |

And finally, let’s collect the Spotify popularity rankings for each artist:

| artist | popularity |

|---|---|

| Chappell Roan | 87 |

| Beyoncé | 87 |

| Fleetwood Mac | 83 |

| Fred again.. | 79 |

| U2 | 79 |

| Jamie xx | 73 |

| Charli XCX | 67 |

| Barry Can’t Swim | 64 |

| NOTION | 63 |

| Bicep | 62 |

| Caribou | 59 |

| Bombay Bicycle Club | 57 |

| DJ Heartstring | 56 |

| Mall Grab | 56 |

| Tourist | 54 |

| salute | 54 |

| Jasper Tygner | 47 |

| SWIM | 46 |

| Tom VR | 35 |

| TC4 | 18 |

My data is, as I mentioned, a different dataset from Spotify’s, but it is interesting to see how much the artists move around when ranked differently.

Are top artists biased toward popular artists? #

Several folks I’ve talked to about Spotify Wrapped have speculated that it’s biased toward the popular artists. Looking at my top artists with these different rankings, it seems to me that popularity could be contributing to the ranking, and therefore the top 5 artists selection.

Let’s test this out with a I didn’t really know what this looked like in practice but thankfully I asked for help sorting through my ideas so now I get to say fancy things like this. …

If you don’t want to read the detailed analysis, feel free to skip to the findings!

Equal weights #

First, let’s test out equal weights for listen frequency, listen consistency, and artist popularity:

(listens * 1)

+

(days_listened * 1)

+

(artist_popularity * 1)

This yields the following ranking:

| artist | equal_weights |

|---|---|

| TC4 | 292 |

| SWIM | 275 |

| DJ Heartstring | 254 |

| Beyoncé | 250 |

| Tourist | 231 |

| U2 | 230 |

| Bicep | 204 |

| Chappell Roan | 202 |

| Caribou | 201 |

| Jamie xx | 194 |

| Charli XCX | 184 |

| Fleetwood Mac | 175 |

| NOTION | 175 |

| Barry Can’t Swim | 168 |

| Mall Grab | 167 |

| Fred again.. | 160 |

| Jasper Tygner | 158 |

| Bombay Bicycle Club | 153 |

| salute | 145 |

| Tom VR | 129 |

Using equal weights for each metric gets pretty close to the actual Spotify top 5, but I’m curious how it changes with uneven weights.

Popularity as more important #

Next, let’s test out adding more weight to popularity, using 20% as a way to provoke an obvious but not unreasonably high change:

(listens * 1)

+

(days_listened * 1)

+

(artist_popularity * 1.2)

That calculation yields the following ranking:

| artist | upweight_popularity |

|---|---|

| TC4 | 295.6 |

| SWIM | 284.2 |

| Beyoncé | 267.4 |

| DJ Heartstring | 265.2 |

| U2 | 245.8 |

| Tourist | 241.8 |

| Chappell Roan | 219.4 |

| Bicep | 216.4 |

| Caribou | 212.8 |

| Jamie xx | 208.6 |

| Charli XCX | 197.4 |

| Fleetwood Mac | 191.6 |

| NOTION | 187.6 |

| Barry Can’t Swim | 180.8 |

| Mall Grab | 178.2 |

| Fred again.. | 175.8 |

| Jasper Tygner | 167.4 |

| Bombay Bicycle Club | 164.4 |

| salute | 155.8 |

| Tom VR | 136 |

That chart looks basically identical to the original chart, with Beyoncé and U2 jumping up but many artists staying in roughly the same region.

Consistency as unimportant #

Another consideration is whether consistency is actually a factor at all in determining the top artists. Let’s try downweighting it in the calculation, with other weights being equal:

(listens * 1)

+

(days_listened * 0.8)

+

(artist_popularity * 1)

These results look even more similar to the original top 5 list:

| artist | downrank_consistency |

|---|---|

| TC4 | 279.6 |

| SWIM | 261.8 |

| Beyoncé | 246.6 |

| DJ Heartstring | 242.6 |

| U2 | 227.6 |

| Tourist | 223 |

| Chappell Roan | 197.2 |

| Bicep | 196.8 |

| Caribou | 194 |

| Jamie xx | 187.2 |

| Charli XCX | 177 |

| Fleetwood Mac | 172.8 |

| NOTION | 166 |

| Mall Grab | 160.8 |

| Barry Can’t Swim | 159.8 |

| Fred again.. | 154.6 |

| Jasper Tygner | 150.6 |

| Bombay Bicycle Club | 148.4 |

| salute | 139.2 |

| Tom VR | 121.2 |

Actually, let’s try just excluding consistency entirely:

(listens * 1)

+

(artist_popularity * 1)

That calculation produces the following ranking:

| artist | exclude_consistency |

|---|---|

| Beyoncé | 233 |

| TC4 | 230 |

| U2 | 218 |

| SWIM | 209 |

| DJ Heartstring | 197 |

| Tourist | 191 |

| Chappell Roan | 178 |

| Bicep | 168 |

| Caribou | 166 |

| Fleetwood Mac | 164 |

| Jamie xx | 160 |

| Charli XCX | 149 |

| Mall Grab | 136 |

| Fred again.. | 133 |

| NOTION | 130 |

| Bombay Bicycle Club | 130 |

| Barry Can’t Swim | 127 |

| Jasper Tygner | 121 |

| salute | 116 |

| Tom VR | 90 |

That looks much closer to my actual Spotify top 5. Let’s see if upweighting popularity is even closer. This time, I’ll upweight popularity by 30%, because it’s a proxy for newness as well:

(listens * 1)

+

(artist_popularity * 1.3)

That calculation produces these final rankings:

| artist | upweight_popularity |

|---|---|

| Beyoncé | 259.1 |

| U2 | 241.7 |

| TC4 | 235.4 |

| SWIM | 222.8 |

| DJ Heartstring | 213.8 |

| Tourist | 207.2 |

| Chappell Roan | 204.1 |

| Fleetwood Mac | 188.9 |

| Bicep | 186.6 |

| Caribou | 183.7 |

| Jamie xx | 181.9 |

| Charli XCX | 169.1 |

| Fred again.. | 156.7 |

| Mall Grab | 152.8 |

| NOTION | 148.9 |

| Bombay Bicycle Club | 147.1 |

| Barry Can’t Swim | 146.2 |

| Jasper Tygner | 135.1 |

| salute | 132.2 |

| Tom VR | 100.5 |

I think as long as I’m using the Last.fm data, I won’t be able to shake Caribou and Tourist out of their spots above Charli XCX. I bought both their albums, and Caribou had an excellent Boiler Room set to boot.

Correct for listening activity #

What I can do is to adjust the rankings to account for what I know about my listening activity. The ranking with upweighted popularity and no accounting for consistency of listens seems pretty close to the Spotify top 5, so let’s start there, then assign corrections for artists that don’t fit:

| artist | upweight_popularity | correction |

|---|---|---|

| Beyoncé | 259.1 | keep |

| U2 | 241.7 | keep |

| TC4 | 235.4 | exclude |

| SWIM | 222.8 | exclude |

| DJ Heartstring | 213.8 | exclude |

| Tourist | 207.2 | downrank |

| Chappell Roan | 204.1 | downrank |

| Fleetwood Mac | 188.9 | exclude |

| Bicep | 186.6 | downrank |

| Caribou | 183.7 | downrank |

| Jamie xx | 181.9 | downrank |

| Charli XCX | 169.1 | keep |

| Fred again.. | 156.7 | downrank |

| Mall Grab | 152.8 | exclude |

| NOTION | 148.9 | exclude |

| Bombay Bicycle Club | 147.1 | exclude |

| Barry Can’t Swim | 146.2 | downrank |

| Jasper Tygner | 135.1 | downrank |

| salute | 132.2 | downrank |

| Tom VR | 100.5 | exclude |

Any artist labeled exclude is one that I either didn’t listen to on any streaming services, or didn’t listen to on Spotify specifically, choosing to listen on SoundCloud or YouTube instead. My listening to Fleetwood Mac specifically took place outside the time window for Spotify Wrapped, so I’ll also exclude that activity.

Any downranked artists are those whose music I purchased, but still listened to on Spotify at least some of the time by my recollection.

Let’s remake the table, assessing a 30% tax to downrank the relevant artists accordingly:

| artist | revised_rank |

|---|---|

| Beyoncé | 259.1 |

| U2 | 241.7 |

| Chappell Roan | 176.8 |

| Charli XCX | 169.1 |

| Tourist | 166.1 |

| Jamie xx | 155.8 |

| Bicep | 154.8 |

| Caribou | 151.6 |

| Fred again.. | 140.5 |

| Barry Can’t Swim | 127.3 |

| salute | 113.6 |

| Jasper Tygner | 112.9 |

The listen volumes of Bicep and Jamie xx and the popularity and listen volume of Chappell Roan couldn’t be totally caught, but with this added adjustment we can pretty closely approximate the Spotify top 5 artists. Here’s the full methodology that I used to produce this result:

- Start with a list of the top 20 most listened to artists according to Last.fm

- Ignore any details about listen consistency

- Weight artist popularity by an added 30%

- Exclude any listening activity that occurred fully off Spotify

- Downrank any listening activity that mostly occurred off Spotify by discounting it by 30%%

Or, as a formula:

(listen_frequency * if(rank = "keep", 1, rank="downrank", 0.7))

+

(artist_popularity * 1.3)

With these data correction and weighting tactics, I can effectively re-rank my most-listened-to artists and end up with nearly the same top 5 artists as Spotify.

I didn’t need to do a bunch of fake math to attempt to replicate my top 5 artists, but I wanted to, so here we are.

The anecdata agree #

Some anecdata from friends support a bias toward popularity, but also some artists or tracks missing that they’d expect to see represented. Algorithmic weighting by popularity might account for some of that, but it’s also possible that Spotify does some filtering.

At first, I thought that maybe the filtering would be to weight by newness to favor artists that released music in 2024, but the popularity metric alone might be enough to weight by newness because newness directly contributes to the popularity score.

The documentation for the get_track API endpoint clarifies:

The popularity is calculated by algorithm and is based, in the most part, on the total number of plays the track has had and how recent those plays are.

Generally speaking, songs that are being played a lot now will have a higher popularity than songs that were played a lot in the past. Duplicate tracks (e.g. the same track from a single and an album) are rated independently. Artist and album popularity is derived mathematically from track popularity. Note: the popularity value may lag actual popularity by a few days: the value is not updated in real time.

Maybe if I’d listened intensely to a less popular U2 album, or to a more obscure album by another artist, my weeklong U2 deep dive wouldn’t have appeared at all. Or perhaps no matter the artist popularity, the listening intensity was too all-consuming to exclude.

For some people that shared their experiences, some clear consistent listening habits were missing:

- Listening to Elliott Smith (

popularity = 68) a lot after the election (which is when my U2 listening happened). - Listening to classic rock and folk music like Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (

popularity = 61) or Joni Mitchell (popularity = 64) regularly throughout the year.

And my personal favorite:

- Listening to Monster Mash (

popularity = 70) once every day.

For these people, these tracks and artists didn’t appear on their Spotify Wrapped at all (Monster Mash was supplanted by Chappell Roan’s track Good Luck, Babe, which has a popularity of 93).

It could also be that in an attempt to highlight new and popular tracks and make Spotify Wrapped feel like a true wrap up of a particular year, consistent listening to Released at least 18 months ago. might be downranked in favor of artists that were new to the user that year.

In 2022, Spotify did account for how much of a user’s listening activity was to catalog music or to new music as part of their Listening Personality assignments, so it’s not a new thing for Spotify to account for, algorithmically.

My top tracks of 2024 #

Now that we’ve dug into my top artists of the year, what were my top 5 tracks of 2024 according to each service?

| Spotify | SoundCloud | Last.fm |

|---|---|---|

| Jamie xx, Honey Dijon - Baddy On The Floor | SWIM - ID - freddie’s island | Bicep - CHROMA 001 HELIUM |

| Caribou - Broke My Heart | Mixmag - Impact: Interplanetary Criminal | U2 - Running to Stand Still |

| Caribou - Honey | SWIM - ID - don’t | U2 - I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For |

| Jamie xx - Treat Each Other Right | SWIM - ID - moveit | Jamie xx - Treat Each Other Right |

| U2 - Running To Stand Still | SWIM - ID - slowdown | Jamie xx - Baddy On The Floor |

SoundCloud doesn’t provide a list of top tracks in its statistics, so these are the first 5 tracks in the Playback playlist.

The good news is that I enjoyed all of these songs enough this year to purchase all of them, except for the Mixmag DJ set with Interplanetary Criminal because it is not a song.

It took me a few days to decide that I should probably just buy U2’s Joshua Tree rather than listen to the same 4 songs on repeat the day after the election. I preordered both Caribou and Jamie xx’s new albums, and I was disappointed that both of them ended up releasing 4-5 tracks off the album as singles before the album came out, but that did make it easier for those singles to show up higher in my listening habits.

Given that Jamie xx was releasing an album for the first time in a while, a lot of my listens to Jamie xx were evaluative — do I like this track? do I like this new direction? — rather than listening to the songs because I already liked them. That led to a different kind of repeat listening than the U2 tracks in the top 5 did, which showed up because they were hitting the right brain groove at the right time.

SWIM released his IDs album after I had spent a few weeks listening to a few of his sets on YouTube where he was playing mostly those IDs, so when they came out I definitely consumed them, although they were released on Bandcamp first (where I bought them) before SoundCloud. I still listened to them on SoundCloud while at work, so I could see this prominence making sense.

My total listening activity on SoundCloud was only about half as much as on Spotify, so the playback is also drawing from a smaller pool of music to remind me about, and a lot of that pool is made up by DJ sets too.

While 2 of my top songs of 2024 according to Spotify were by Jamie xx, he didn’t appear in my top 5 artists of the year. Because his popularity score is higher than both Tourist and Caribou, I don’t think it’s a matter of popularity bias. A more likely explanation is that I preordered his album, so after his album came out I converted most of my listening activity to my personal devices rather than continuing to stream on Spotify.

My top song of 2024 #

According to Spotify, my top song was Baddy on the Floor by Jamie xx and Honey Dijon, which I listened to 16 times.

That listening activity put me in the top 0.05% of listeners worldwide. According to Spotify, I first streamed it on April 22, 2024, which is a week after its release date.

Let’s check in with Last.fm to see how that matches up:

- I listened to the track 23 times in total.

- I first listened to the track on April 21, 2024 at 17:03:45, so while I first heard it on Spotify on April 22, I’d already heard the song by then, likely on Bandcamp.

- Spotify counts a track as “streamed” if you listen to at least 30 seconds of the track, so that could be part of why their count seems somewhat high here.

Perhaps I really did just stream it 16 times on Spotify while trying to decide if I liked it or not. I also recall a few times when the autoplay suggestion after a playlist finished was this track, which is somewhat of a self-reinforcing way to get to top song of the year — the algorithm made it so.

According to Last.fm, my actual top song in terms of total listens is CHROMA 001 HELIUM by Bicep, with 25 total listens.

This surprised me, but likely means that I’m extremely ready for Bicep to put out a new album. Just a few years ago, Bicep dominated my top songs of 2020.

How the playlist gets made #

Given the different weights and contributors that might affect the top artists ranking, I was curious if similar factors might affect the “Your Top Songs 2024” playlist.

The Spotify Wrapped support page is specific yet vague:

Is the ‘Your Top Songs 2024’ playlist in order of what I listened to most?

Yes, it’s ordered by the songs you played most frequently to least frequently.

It isn’t confirmed that the top songs playlist is the exact songs that you played, from most frequent to least frequent, but the tracks that are included are in frequency order. It’s probably easiest to pull the data that way, but in an effort to make the playlist more varied and representative of someone’s year, there might be some amount of curation or filtering happening.

Given the prominence of SWIM and Club Angel on my SoundCloud Playback, I think SoundCloud is sticking to the basics.

If I compare the first 40 tracks or so from the Spotify Your Top Songs 2024 playlist to my most-listened to tracks on Last.fm, some evidence of my listening habits are revealed:

- Tracks from albums that I evaluated on Spotify show up on the playlist, such as those from Beyoncé, Fred again.., Charli XCX, Caribou, and Tourist.

- Tracks that I discovered while compiling DJ set playlists based on Shazams also showed up on the list.

- Tracks that I discovered from other playlists, like the South African Jams playlist that Rian van der Merwe put together and shared on his blog in January, also appeared.

Meanwhile, the broader picture of my listening captured by Last.fm includes:

- A post-November 15 deep dive into Fleetwood Mac’s album Rumours

- Being dedicated to SWIM’s album and DJ Heartstring’s releases.

- Enjoying the artists whose albums I bought this year, like Beyoncé, Caribou, Tourist, and Jamie xx.

Many of the same songs are in the top 20 tracks for each service, but at different rankings:

Total songs heard in 2024 #

Spotify says I listened to a total of 2,616 songs this year. According to my own records, I listened to at least 8,949 and counting. Even shaving off a few for potential duplicates or miscounts, that’s an order of magnitude larger. My attempts to listen to more music offline, and off Spotify, continue to succeed.

Total minutes listened in 2024 #

For each service, here’s how many minutes of music I ostensibly listened to:

| Spotify | SoundCloud | Estimated total |

|---|---|---|

| 14,248 | 6,055 | 59,948 |

For both Spotify and SoundCloud, it’s unclear to me if the minutes listened are the actual number of minutes that I listened to music, or a more basic calculation of:

(track_name * track_duration) * listen_count

I’d wager it’s the formula, if only because it’s simpler to calculate on the fly, but it really comes down to what level of granularity of user activity is stored and made accessible for compiling these stats. Spotify also counts offline listening, but I’m not sure if SoundCloud does (which, if not, many hours of DJ sets are missing).

As part of user session data, Researchers at Spotify published a dataset, The Music Streaming Sessions Dataset with an accompaning paper that mentions three different skip tracking behaviors: skip 1, indicating whether the track was only played very briefly, skip 2, indicating whether the track was only played briefly, and skip 3, indicating whether most of the track was played, as well as not skipped. . SoundCloud, on the other hand, counts a track as played “once the play button is clicked” according to Insights basics – SoundCloud Help Center.

My own estimated minutes calculation is based on an estimate made with the assumption that if I listened to the track, I listened to the entire track. This is partially based on the fact that a Last.fm listening event (a scrobble) is recorded if a track is longer than 30 seconds and “the track has been played for at least half its duration, or for 4 minutes (whichever occurs earlier.)”

To calculate an estimate of minutes listened, I use the following methodology. For each track that I listen to:

- If a matching track exists in my music library, use the actual track duration.

- If a match does not exist (which could be due to mismatched metadata), use a constant value equivalent to the mean average track duration of all matched tracks listened to in 2024.

For 2024, that mean average track duration is about 4.45 minutes, or 4 minutes, 27 seconds.

Notably, any DJ set or concert recording that I listened to on YouTube or SoundCloud is totally misrepresented in this data. For example, I listened to Chappell Roan’s Bonnaroo set at least 14 times.

With this estimate, those 14 listens would contribute about 62.3 minutes to my total for the year.

In reality, that Bonnaroo set recording is 58 minutes and 22 seconds long. Listening to that 14 times is 817.13 minutes — a difference of more than 13 times.

Returning to the Spotify Wrapped data, my biggest listening day was October 11, with 404 total minutes listened.

If I look at my overall listening behavior, and factor in the estimated time spent listening each day, I get the following:

| day | listens | length (minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| Jun 10, 2024 | 113 | 503 |

| Apr 03, 2024 | 110 | 490 |

| Jun 25, 2024 | 108 | 481 |

| Oct 30, 2024 | 105 | 467 |

| Oct 04, 2024 | 103 | 458 |

| May 01, 2024 | 93 | 414 |

| Jun 05, 2024 | 93 | 414 |

| Apr 23, 2024 | 89 | 396 |

| Apr 08, 2024 | 87 | 387 |

| Jul 10, 2024 | 86 | 383 |

| Sep 06, 2024 | 86 | 383 |

| Apr 05, 2024 | 85 | 378 |

| Oct 09, 2024 | 84 | 374 |

| Jul 23, 2024 | 83 | 369 |

| Oct 10, 2024 | 83 | 369 |

| Dec 04, 2024 | 82 | 365 |

| Jan 18, 2024 | 81 | 360 |

| Jun 08, 2024 | 80 | 356 |

| Oct 11, 2024 | 78 | 347 |

October 9, 10, and 11 were popular days for lots of music listening, it turns out.

347 estimated minutes compared to 404 ostensible Spotify minutes isn’t bad, but let’s see how much time I spent listening to Chappell Roan’s Bonnaroo set alone:

| day | track_name | listens | length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aug 13, 2024 | Bonnaroo 2024 (Full Set) | 5 | 291.8 |

| Aug 14, 2024 | Bonnaroo 2024 (Full Set) | 2 | 116.7 |

| Aug 21, 2024 | Bonnaroo 2024 (Full Set) | 2 | 116.7 |

| Aug 30, 2024 | Bonnaroo 2024 (Full Set) | 2 | 116.7 |

| Jul 30, 2024 | Bonnaroo 2024 (Full Set) | 1 | 58.37 |

| Aug 01, 2024 | Bonnaroo 2024 (Full Set) | 1 | 58.37 |

| Aug 26, 2024 | Bonnaroo 2024 (Full Set) | 1 | 58.37 |

That’s over 817 minutes spent listening to that set, with over a third of that listening happening on August 13, 2024.

While Spotify thinks that October 11, 2024 was a big day for music listening, as far as I can tell, it was a typical Friday at work. On the other hand, June 10, 2024 (my highest listening day according to Last.fm) was a typical Monday as well. Mysterious.

SoundCloud and my top genres #

I usually compare my top genres, but

It’s pretty disappointing, but their genre data also does evolve over time which would have been interesting to dig into. In 2020 I noted the genres associated with Tourist and those are basically the same except that tropical house and shimmer pop are gone but future garage has been added, and electronica has been replaced with indietronica.

, so instead I’ll compare my SoundCloud genres with the genres associated with my iTunes purchases. Unfortunately, Bandcamp purchases don’t contain a lot of metadata, so I don’t have any genre data for the hundreds of tracks I purchased there.

| SoundCloud | Total minutes | iTunes genre | Total tracks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic (Jasper Tygner) | 4625 | Electronic | 27 |

| Pop (Romy) | 489 | Dance | 22 |

| Hip Hop (Misael Deejay) | 500 | Pop | 14 |

| Afrobeat (Heisrema) | 223 | Alternative | 11 |

| Folk (Snow Patrol) | 218 | R&B/Soul | 10 |

The SoundCloud playback genres really underscore what a difficult problem it is to have clean, consistent, and high quality metadata for music.

Misael Deejay was the artist listed as the representative artist for my Hip Hop listening, but I haven’t liked a single one of his tracks on SoundCloud. I was pretty confused, but then I realized that the only track of his that I listened to is the track I Have a Love (Overmono Remix) 3 times. That track is actually a remix of a track by the artist For Those I Love. This is a total bootleg track—I didn’t actually listen to Hip Hop this year.

Sorry SoundCloud, metadata is hard.

SoundCloud also took the time to share the top 5 moods of the music that I’ve listened to this year:

- energetic

- powerful

- relaxed

- quirky

- exciting

Unlike the genres, these moods weren’t associated with any specific artists. I’d love to investigate further (what is quirky?!) but SoundCloud doesn’t provide API keys to their service or publish much about their research on their developer blog, Backstage, or on their official company site.

Some other mysterious moods that friends noted are “angry” and “dark”. I’ll keep brainstorming other sources I can use to dig into this further, but for now it’s tough to say where those moods are coming from.

Spotify’s “Music Evolution” #

Spotify usually includes something special in Wrapped every year.

- In 2023 it was streaming habits such as “Alchemist… you create playlists more than other listeners do” and a “sound town”.

- In 2022, it was my listening personality (the specialist) and my “audio day”.

- In 2021, it was an audio aura, with some music moods (ecstatic and innovative).

- In 2020, there wasn’t a special thing, but there were stats about artist and genre discovery that haven’t resurfaced.

- In 2019, Spotify wrapped up the entire decade and also shared geographic information.

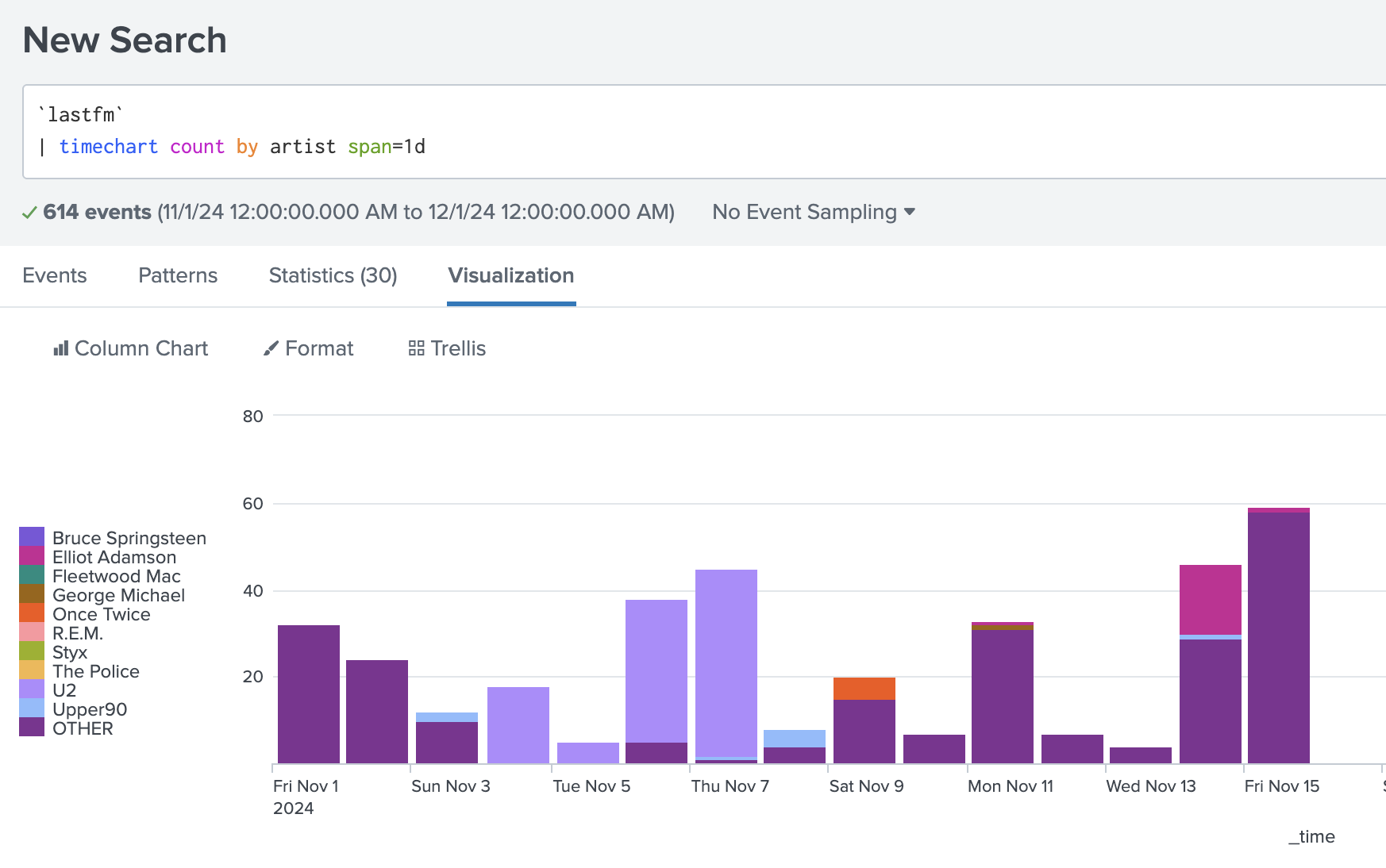

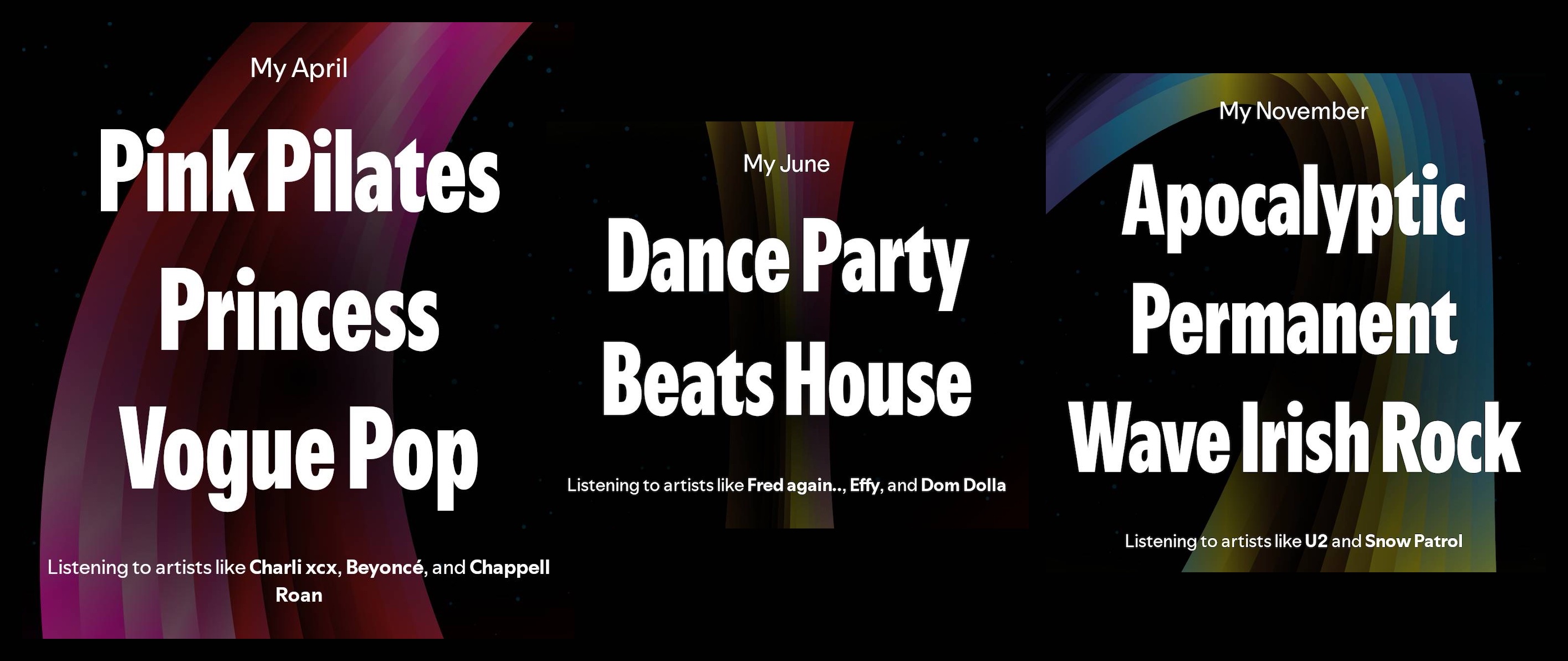

This year, Spotify focused on your “Music Evolution”, calling out specific months that represented a different type of listening than you usually do. I felt like the evolutions captured three distinct patterns of listening for me this year — my pop music phase, my dance music phase, and my “oops I’m suddenly obsessed with U2’s the Joshua Tree” phase.

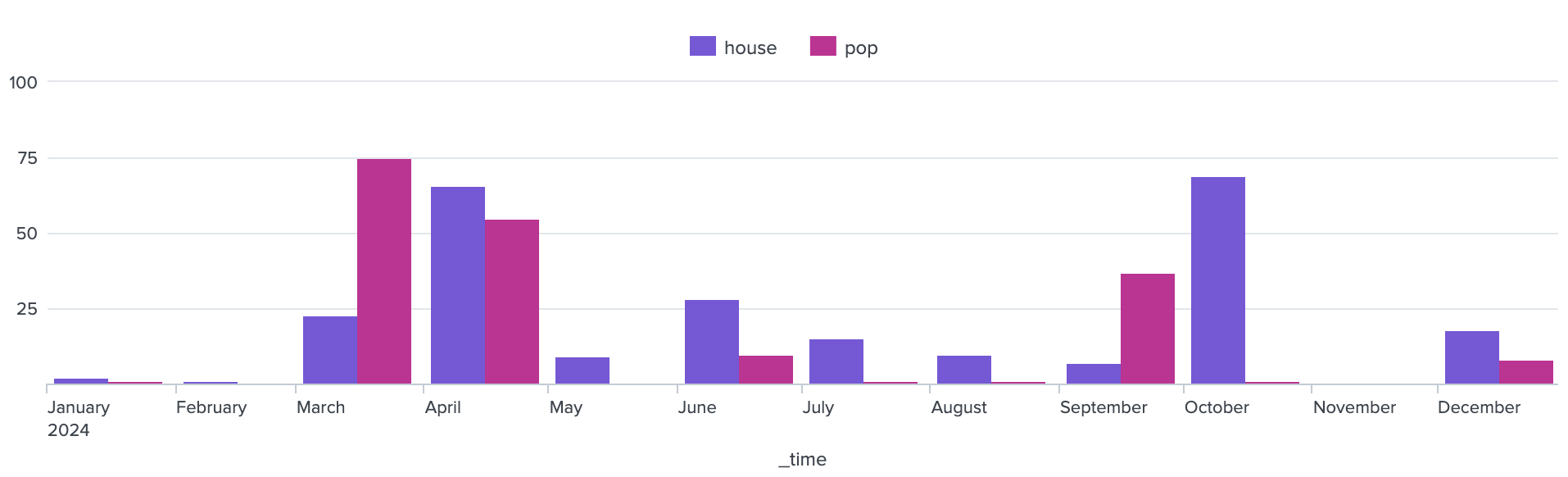

While I certainly had these phases of listening, they didn’t necessarily align with specific, well-separated months. My taste can shift from day to day or week to week, and doesn’t necessarily stay. For example, let’s look only at the top 4 pop artists and top 4 house artists that I listened to this year:

So where did these descriptions actually come from?

Making sense of the music evolution descriptors #

Each year, I attempt to deduce the origin of and contributing factors to the “special thing” included in Wrapped. This year, I wanted to try to determine where the descriptors actually came from, and how loosely or tightly they might be associated with specific artists.

According to Spotify, I had the following musical evolutions:

| Month | Descriptor | Artists |

|---|---|---|

| April | Pink Pilates Princess Vogue Pop | Charli XCX, Beyoncé, Chappell Roan |

| June | Dance Party Beats House | Fred again.., Effy, Dom Dolla |

| November | Apocalyptic Permanent Wave Irish Rock | U2, Snow Patrol |

Lots of new-to-me phrases here (what is Permanent Wave?). I don’t really remember listening to Dom Dolla in June at all, and I think there are better artists and genres to associate with that month of listening. According to Last.fm I listened to him 6 times this year generally, and only once in June.

I probably didn’t listen to much music in June on Spotify. My top 15 artists by listens for that month were the following:

| artist | listens |

|---|---|

| TC4 | 95 |

| Swim | 50 |

| DJ Heartstring | 32 |

| Charli XCX | 25 |

| Bicep | 20 |

| O’Flynn | 20 |

| Barry Can’t Swim | 19 |

| Elkka | 18 |

| Jamie xx | 18 |

| dj poolboi | 17 |

| Tourist | 16 |

| Diffrent | 15 |

| Thelma | 14 |

| sjowgren | 13 |

| Caribou | 12 |

Fred again.., Effy, and Dom Dolla don’t make the list.

As I scrolled through social media, I enjoyed the other music evolutions that I saw posted — and for the most part, I saw a bunch of different descriptors:

Many of the descriptors refer to genres, while others involve vibes or aesthetics, and still others refer to places, activities, and instruments:

| Pink Pilates Princess Strut Pop | Gyaru Jam Band J-Pop |

| Wild West Mandolin Bluegrass | Indieheads Banjo Indie Rock |

| Theatrical Bandolim Choro | Pink Pilates Princess Strut Pop |

| Pink Pilates Princess Strut Pop | Scene Old School Emo Post-Hardcore |

| Breakup Banjo Folk Punk | Academic Permanent Wave Rock |

| Pink Pilates Princess Strut Pop | Mallgoth Skateboarding Punk |

| McBling Hollywood Pop | Serotonin Alt Z Indie Pop |

| Atmospheric Fantasy Soundtrack | Atmospheric Tavern Fantasy Music |

| Chill Beats Lo-Fi | Theatrical West End Broadway |

| Pink Pilates Princess Roller Skating Pop | Indie Sleaze Strut Pop |

| Pyschedelic Mid-Tempo Balearic Beat | Lounging Microtonal Neo-Psychedelic |

| After Hours Hollywood Pop | Academic Beats Edm |

| Wanderlust Metropolis Indie Pop | Pink Pilates Princess Strut Pop |

| Pink Pilates Princess Vogue Pop | Dance Party Beats House |

| Apocalyptic Permanent Wave Irish Rock | Pink Pilates Princess Catwalk Pop |

Some categories that I’ve defined here can be debated (is lounging more of a vibe or an activity?) but the words mostly maintain a strong association with music. Some full descriptors double up on the genre names, like “Permanent Wave Irish Rock” or “Emo Post-Hardcore”.

Looking at this full list, however, you might have noticed a pattern…

What is up with the Pink Pilates Princess #

Of the music evolutions that I saw online from friends, there were a lot of interrelated descriptors, so I compiled a list of similar ones based on what I saw on social media and that friends shared with me:

- Pink Pilates Princess Strut Pop

- Pink Pilates Princess Roller Skating Pop

- Indie Sleaze Strut Pop

- Indie Sleaze Roller Skating Pop

- Pink Pilates Princess Catwalk Pop

- Pink Pilates Princess Vogue Pop

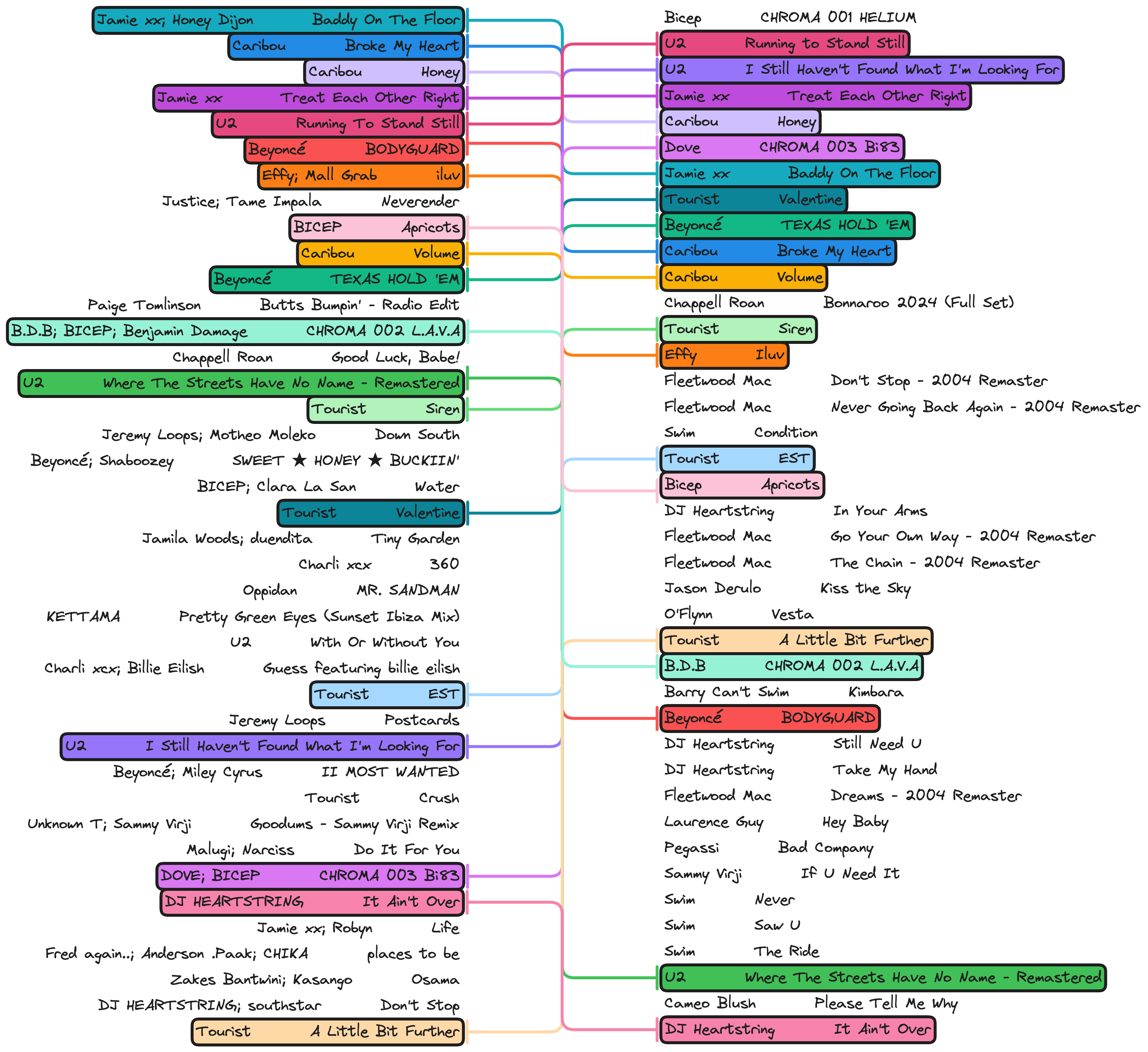

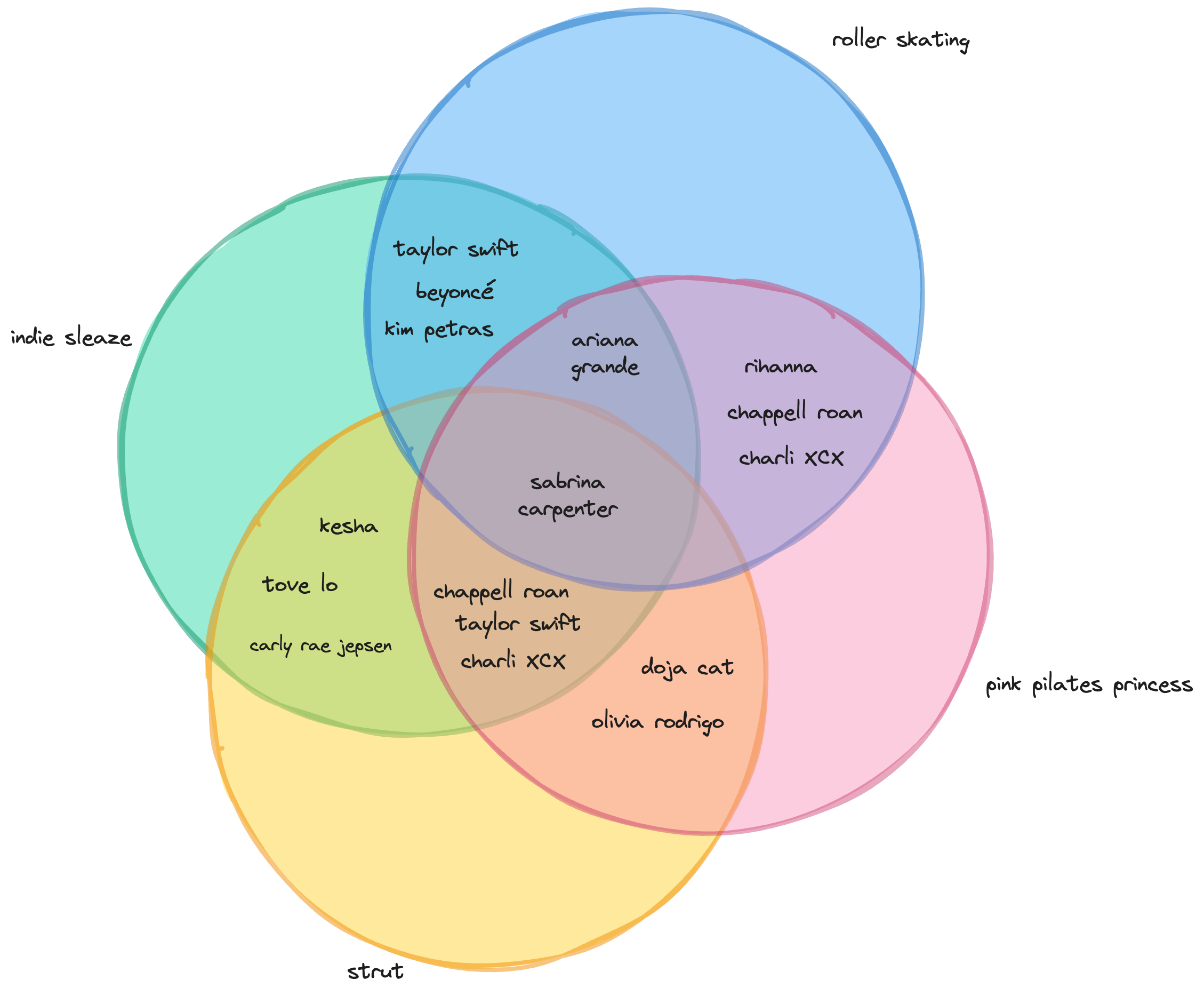

The amount of overlap led me to make this venn diagram of artists associated with various descriptors:

Sabrina Carpenter has the honor of being in all 4 evolution categories, but she’s Charli XCX, Chappell Roan, and Taylor Swift nearly did too, but neither Charli nor Chappell showed up in any Indie Sleaze Roller Skating Pop examples that I found, and Taylor didn’t show up for any Pink Pilates Princess Roller Skating Pop examples that I found. Sample size is small, but nonetheless. that matched all four:

- Indie Sleaze Strut Pop

- Indie Sleaze Roller Skating Pop

- Pink Pilates Princess Roller Skating Pop

- Pink Pilates Princess Strut Pop

While it’s clear that Pop is a genre, Indie Sleaze and Pink Pilates Princess were such discrete phrases that I figured they would be derived from playlist names, probably of the artists that were represented in those categories.

I went digging into the featured playlists for each artist, and discovered the Hot Pink playlist which seems to borrow a name from a Doja Cat album and features many of the artists on the list, but it is also listed as “Made for Sarah Moir”, so it seems to be algorithmically generated as well.

Indie Sleaze is a playlist, but none of the artists in Indie Sleaze Strut Pop or Indie Sleaze Roller Skating Pop are on it!

If I search for Pink Pilates Princess, I get a hit — but it’s a Pink Pilates Princess Mix, and seems to be an AI playlist a la Spotify Premium Users Can Now Turn Any Idea Into a Personalized Playlist With AI Playlist in Beta.

Neither Strut nor Roller Skating were playlists. I thought maybe Sabrina Carpenter might have made a music video where she roller skates, but I couldn’t find any evidence that these phrases were associated in any way with the artists.

Spotify does collect cultural metadata about music, but it isn’t publicly available. It’s possible that these descriptor phrases were derived from cultural metadata that were associated with these artists in album review blog posts, TikTok tags, or social media post descriptions about the artists.

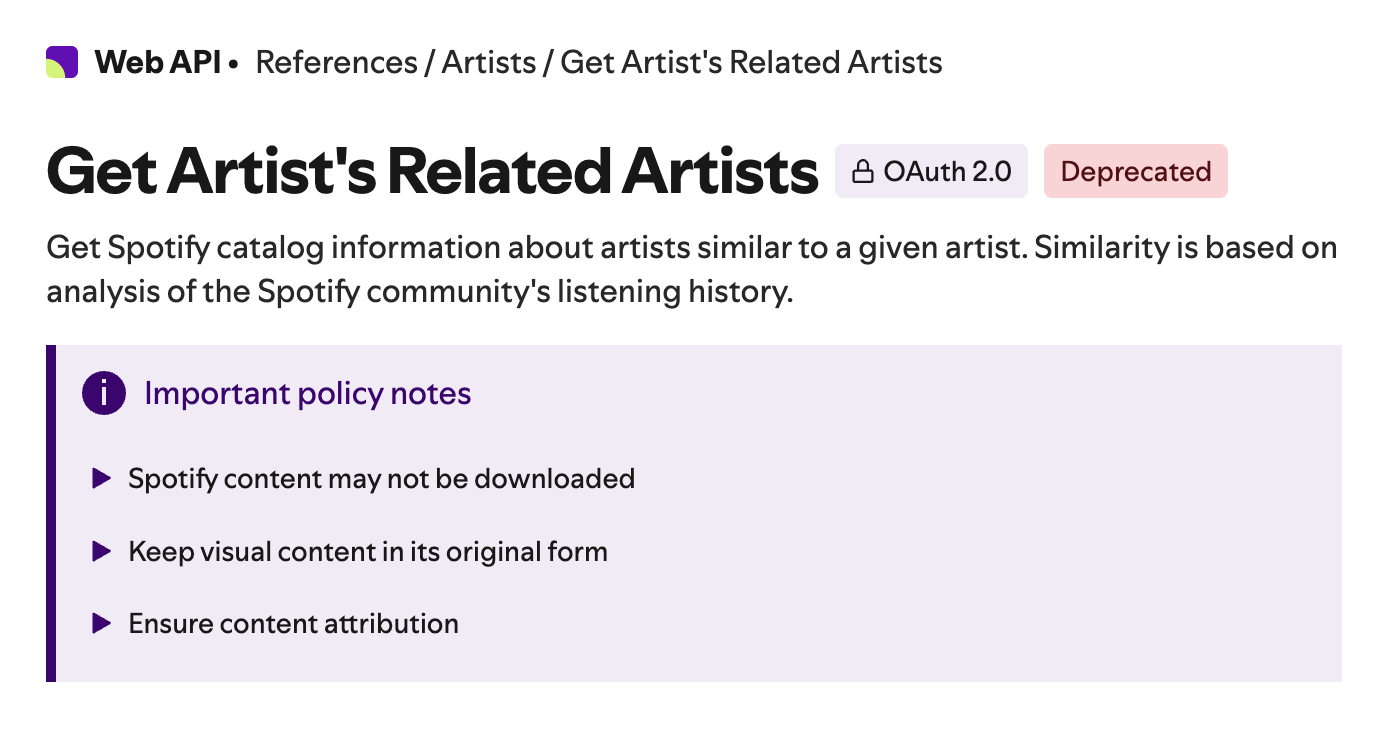

Finally, to see whether the artists themselves had similar interrelationships from a metadata perspective as their categorizations might seem to imply. With Charli XCX and Chappell Roan having the same three descriptors while Sabrina Carpenter is in all four, I wanted to dig into the related artists for each artist to determine how tightly they might be webbed together.

Unfortunately, when I went to explore this further, I discovered that the Get Artist’s Related Artists API endpoint for the Spotify API has been deprecated for “security reasons” just a few weeks ago.

As a result, the API endpoint isn’t available from the documentation and is only available for folks with an API key that is out of “development” mode (which mine is not). Introducing some changes to our Web API on the Spotify for Developers site has more details.

Where did the music evolution descriptors come from? #

That was all my speculation, but the official Spotify blog in Everything You Need To Know About Your Music Evolution says exactly how the music evolution phases were identified and how the titles were crafted:

Several special factors went into creating Your Music Evolution, including the amount of time you spent listening to an artist or genre, peak listening months, and distinctiveness, which means spotlighting a genre that stood out from your usual listening patterns.

- Spotify combined machine learning with human curation to associate descriptors and genres with different tracks. These descriptors then informed your musical phases.

Specifically vague. Human curation to me here means “data labeling”, with machine learning doing some generation and assignment of descriptors possibly influenced by cultural metadata. However, these word soup descriptors aren’t new to Spotify.

Ancestors of Music Evolution: daylist and Audio Day #

When I first saw my music evolutions, I was like “oh this is basically just daylist”, the already unhinged playlist descriptions that Spotify has been creating since September 2023.

In Get Fresh Music Sunup to Sundown With daylist, Your Ever-Changing Spotify Playlist, Spotify introduces the daylist:

Say hello to daylist, your day in a playlist. This new, one-of-a-kind playlist on Spotify ebbs and flows with unique vibes, bringing together the niche music and microgenres you usually listen to during particular moments in the day or on specific days of the week. It updates frequently between sunup and sundown with a series of highly specific playlists made for every version of you. It’s hyper-personalized, dynamic, and playful as it reflects what you want to be listening to right now.

Given that the playlist is pitched as hyper-personalized, it’s not surprising that it’s also AI-generated.

In a NYTimes article, That Spotify Daylist That Really ‘Gets’ You? It Was Written by A.I., Frank Rojas reports:

“Spotify uses machine learning to pull together the thousands of descriptors that create the unique daylist playlist names,” Molly Holder, a senior product director at Spotify, said in a statement. She characterized the tone of the titles as “hyper-personalized, dynamic and playful.”

Ms. Holder added that the team behind these quirky playlists included data scientists and music experts who identify musical descriptors based on genre, mood and themes that are then associated with specific tracks “through methods such as music expert annotation, sonic similarity and trends.”

Put another way, the descriptors are defined by humans, and then assigned to specific tracks by data labelers and algorithms.

For reference, here’s one daylist that was generated while I was writing this post:

The music evolution and daylist descriptors made an earlier appearance in Spotify Wrapped — back in 2022, as an “Audio Day”.

According to the Everything You Need To Know About 2022 Wrapped blog post from Spotify:

Audio Day showcases the niche moods and aesthetic descriptors of the music you listened to during morning, midday, and evening time periods.

My Audio Day looked like this:

In 2022, I also investigated these descriptors. I wrote:

How did Spotify define these “niche moods and aesthetic descriptors”?

Poking around on the Spotify Research blog, I discovered the post The Contribution of Lyrics and Acoustics to Collaborative Understanding of Mood, which points out:

The association between a song and a mood descriptor was calculated using collaborative data, by “wisdom of the crowd”. More specifically, these relationships were derived from Spotify playlists’ titles and descriptions, by measuring the co-occurrence of a given song in a playlist, and the target mood descriptor in its title or description.

Researchers derived mood descriptions based on the titles and descriptions for playlists that songs were added to by Spotify users. Those mood descriptors were used as the baseline for the rest of the research, which explored whether the energy of a song and the lyrical content could be reliably correlated with mood.

And indeed, the findings of the research asserted that:

by combining information extracted from the two modalities – lyrics and acoustics – we can best predict the relationship between a song and a given mood.

I think that, based on the haphazard nature of the descriptions for My Audio Day, these were likely derived from the playlist title and description data source. Spotify is performing this research, however, to improve recommendations and search. Namely:

we want to enable search based on mood descriptors in the Spotify app, for example by allowing users to search for “happy songs”. Additionally, from the recommendations side, we want to be able to recommend new songs to users that provide similar sets of moods users might already like.

The groundwork for AI-curated mood-based playlists, mixes based on a string of words, was already in the research and Spotify Wrapped back in 2022. It’s pretty clear that this is a personalization direction that Spotify has been pursuing for years, starting (possibly) with the Audio Day, becoming widely available with daylist, then even more personalizable with AI playlists, and now the latest iteration with Music Evolution.

The backlash #

I suppose that makes it somewhat surprising to see backlash to Spotify Wrapped this year, and not much over to the AI-driven personalization initiatives that have landed in the past couple years.

I remember when daylist first came out, lots of folks were sharing their daylist screenshots on Instagram and other social media sites, reveling in the weirdness (and rightness) of the descriptions.

However, with the Music Evolution this year, I haven’t seen many friends sharing screenshots of their Music Evolution on social media, and a lot more folks have shared the overall summary slide without bothering to share the Music Evolution.

Why do I think there has been backlash to Music Evolution?

It’s not very accurate #

Most people don’t actually evolve their listening habits very often, let alone 3 times in one year. Some descriptors might apply to specific groups of artists, but those groups of artists might appear together on a workout playlist, or all be part of the same function (album evaluation).

I mentioned earlier how listening tends to serve a purpose, and for most people, their life doesn’t change all that much throughout the year. The exception is people who work more seasonal jobs, but even then.

In addition to whether the descriptors were accurate, the associated artists didn’t seem accurate either. I experienced this, with Dom Dolla being listed in June, and others have commented that their Wrapped seemed especially focused on popular artists, regardless of what their actual (perceived) listening habits were throughout the year.

The descriptors didn’t resonate with people #

A post on Threads by jaiya (@jaiyagill) sums it up neatly:

The vibes were off —

No genres. No auras. No fun insights. It’s giving “Al-generated corporate report”.

Where’s the “OMG same” “I feel seen”conversation starters / community building moments?

It’s not just about numbers; it’s how you turn it into a story people want to share

And they’re exactly right. In previous years, the labels applied to you — you’re an alchemist, you’re a specialist, you have a specific audio aura, your audio day.

This year, I was told that my April was a “Pink Pilates Princess Vogue Pop” moment. I have no idea what that means or what I’m supposed to take away from that. Am I a Pink Pilates Princess? Is vogue pop a new genre?

It’s a mouthful, and because it isn’t grounded in personal experience, it feels rather meaningless and machine-generated.

Chatting with a friend about this, they pointed out that it would be more interesting (and personally relevant) to say something like:

you spent more time listening to pop this summer

and instead we have:

your music taste in July was after hours Hollywood pop

That type of phrasing instead “feels like the algorithm thinks I’m an algorithm and is like “hello fellow algorithm. You just discovered a new genre! I call it “soft new wave indie beats””

Dr Georgie Carroll, who wrote her PhD thesis on music fandom, elaborated on the personalization factor on LinkedIn:

Spotify Wrapped learned a hard lesson today: data isn’t enough.

Excitement built in recent weeks as fans eagerly awaited their Spotify Wrapped. It finally dropped today, and it’s been met with almost universal disappointment. Why? Because while they gave fans their stats, they took away most of the shareable fun that encouraged community and conversation. No more genres, no telling you which city your listening put you in, no auras, or any other kind of magic that made users go “omg hey, me too!”.

By cutting the human workforce that turned data into stories and relatable insights and replacing it with AI, the reactions to Wrapped are showing us why we can’t rely purely on statistics and technology (especially AI) and think it’s enough to make fans stick around. Data is only part of the story. It’s what you do with it that counts.

The AI smelled #

As I mentioned, it’s a bit surprising to see poor reactions to this feature when other AI-based features haven’t yielded similar backlash. So the reactions might be less due to the use of AI itself, but which AI.

Spotify has been using AI and ML almost since its inception. The metadata, machine learning systems, and artificial intelligence have been building Discover Weekly, Release Radar, Daily Mixes, This is… artist playlists, and much much more for years — but not as much generative AI.

In an article for Business Insider republished by Yahoo News, Spotify Wrapped was a flop for some music listeners this year, a Spotify spokesperson commented:

“Wrapped is an experience that fans look forward to every year, and our approach to the data stories did not change this year,” Spotify told BI in a statement.

“We celebrated fan-favorite data stories like Your Top Artist and Top Songs with new insights like longest listening streak and top listening day,” the company said. “We’re always exploring ways to expand Wrapped and bring new data stories to users across more markets.”

Given how Music Evolution felt itself like an evolution of Audio Day and daylist, it makes sense that it was created using the same approach as previous years.

However, this year is the year of “slop” and “hallucinations” and mainstream generative AI. This is also the year that people are reacting especially poorly, associating the descriptors for Music Evolution with the sort of nonsense that a confused AI-powered chatbot might respond with, instead of interpreting it as an insightful personal response.

A feature built to represent a person’s music evolution but described using phrases that have no seeming root in something tangible really does feel like that AI slop, trying to communicate something but just ending up with word soup and melting textures.

Effect of layoffs on quality #

One potential reason for the lack of accuracy, personal resonance, and AI smell of the Music Evolution feature that has been discussed online is the layoffs at Spotify last year.

On December 4, 2023, Spotify announced layoffs of 17% of the company: Spotify to cut 17% of staff in the latest round of tech layoffs.

Several months later, in their April 23, 2024 earnings call, CEO Daniel Ek acknowledged that the layoffs impacted day-to-day operations, but didn’t specify which teams or operations were affected as a result. The layoffs haven’t come up again in later earnings reports.

A viral Instagram reel by hackyourhr attributes it directly to the layoffs:

still good to meet about the 2025 budget..?

good thing a year ago to the day we laid off 1500 people, right?

the Wrapped team? AI really did its thing

so about that, umm, who’s been managing the AI that did Wrapped this year?

It just did its thing.. the AI… the AI did it

but it actually didn’t do it… we cut all those people last year to the day… no one was managing the AI… they got everything wrong…

Music journalist Zel McCarthy posted a thread on Bluesky and Threads making a similar point, writing:

If you’re a Spotify user who is finding the microgenre & geodata of your annual “Wrapped” to be less substantial than usual, there’s a reason why.

A year ago, Spotify laid off most of its employees who worked on genre classification, including folks like data alchemist glenn mcdonald.

The work Glenn and his colleagues would do—analyze vast quantities of musical content ingested on a weekly basis based on its sound, provenance, & audience then convert that analysis into data points—is no longer being done.

Yes, “Wrapped” is a marketing feature, but it presented real information.

While some of this information could theoretically be gathered by AI or other processes, it still requires human brain work.

As Glenn predicted a year ago, without him and his team, any previously automated systems would eventually desist.

And desist they have.

Personally, I have little love for Spotify’s vaunted recommendation algorithm.

In the past, I’ve written about how it reinforces biases, flattens art into product, and actually limits new music discovery while purporting to do the opposite.

Still, depriving the algo of data only makes it worse.

tl;dr your #SpotifyWrapped is lamer this year b/c the tech company where you get your music has divested from music-based research and analytics.

The music world has less information and has lost the means of gathering it in the future… and as of now, there’s nothing we can do to get it back.

I haven’t been able to independently confirm that Spotify laid off most of the folks that perform genre classification (the data labelers I mentioned earlier, in part). Since Zel McCarthy is a journalist, I trust his reporting here, but I still dug around on LinkedIn.

There are still folks that work on Spotify Wrapped, but a number of data scientists and data curators that previously worked on Wrapped — including someone who described their work as being the human-in-the-loop for data curation, sourcing and evaluating data and interpreting datasets — have been laid off.

Others chose to leave. Ajay Kalia (who was a former Echo Nest employee along with glenn mcdonald) left around the same time as the layoffs occurred to start his own business. Kalia was the Product Director for Personalized Experiences, which was responsible for launching Daylist, among other personalized playlist and other initiatives. Molly Holder, who was quoted in the New York Times article about daylist, remains at Spotify working on personalization.

Even without knowing more specifics about who got laid off, the 2024 version of Spotify is focused on being “relentlessly resourceful” and laying off 1500+ people in order to “rightsize” as a noun. 2021, 2022, and 2023 are years when Spotify did wild things like pay someone to read auras and take you to sound town.

This year’s Wrapped shows that a viral marketing campaign isn’t a “set it and forget it” exercise. The data is the interesting part of the insights, but they need to feel relevant and personal. That doesn’t happen with a word salad of insights, and it does seem to require talented people.

Wrapping up… #

Spotify Wrapped is always going to be a marketing exercise first. If you want to truly understand your accurate data, you need to take the quantified self approach of tracking listening activity on Last.fm, or downloading your listening data directly from Spotify and exploring it.

Overall, one consistent point throughout this post is that data isn’t necessarily personalized, but it is personal. Metrics are one layer of a broader picture, but metrics also are what Spotify has built its business on.

Building datasets of listening behavior, profiles of consumers, and packaging that up into advertising verticals serves as the primary engine of Spotify’s revenue. Building metadatasets with algorithmic and human intervention is the foundation of the sticky playlists and mixes, like Discover Weekly, Release Radar, daylist, and more.

But most quantitative metrics are derived metrics. Even something that seems easy to measure, beats per minute (BPM), is derived, and not that accurate all the time.

Despite tracking my listening behavior and habits, I still make a separate list of what my favorite tracks of the year are, which artists I discovered that are new favorites, and identify my favorite DJ sets. I can assess the frequency, consistency, and popularity of what I listen to for days (and I have, writing this post), but that’s not the same thing.

The true personalization is what music means to me, and that can’t be algorithmically derived.