My 2025 in music: A review

I’ve written this post for years — comparing Spotify Wrapped with my Last.fm data, exploring how Spotify put together their music data categories and how the results of Spotify Wrapped doesn’t quite capture my music taste, pointing to my Last.fm data instead (I’m especially proud of last year’s deep dive).

It’s still relevant to compare these different patterns, but in reviewing my 2025 in music, the reading and research I’ve been doing for years culminated in some continued realizations.

This past year, I read Liz Pelly’s book Mood Machine and related coverage and commentary, researched in more depth the music metadata that companies like Spotify derive, compute, and compile alongside user behavior data, and followed Hanif Abdurraqib on Instagram (and thus got I dream of my favorite thinkers getting their own website or blog, and then I consider that the reason social media and even Substack are so popular is that the platforms make it so low-friction to share your thoughts, no matter how well (or ill) considered they might be. ).

As part of that reading, I’ve internalized that while frequency of listens is indicative of something, it isn’t necessarily “favorite” or “best”. Repeat listens can be a proxy for “comforting” or “dissociative” or “nonconfrontational” as often as it might be a proxy for “favorite”.

I’ve spent years evaluating my quantitative music listening habits, but it wasn’t until a few years ago that I started actually Prompted by a friend who sends out his own favorites every year to a huge email thread full of reply-all sharing. .

With all the work I’ve done in data analysis, I’m even more certain that a quantitative approach isn’t the right one to evaluate what music means to me as a listener. I can devise proxy metrics for “best” — “most frequently played”, “fewest skips”, “most playlisted”, or “most purchased” — but those metrics track activities. Quantitative metrics can’t track intent, and certainly can’t track emotion.

What makes music meaningful to me is crafting memories—having lyrics resonate with your lived experience, feeling the intensity of the dynamics in your soul, having a moment where you sit up and go “wow”. And quantitative data can’t capture those experiences.

So in this annual reflection on my music listening habits, let me color in the quantitative data lines a bit more than usual. Let’s review…

My year in music #

I listened to an estimated 33,000 minutes1 of music in 2025. I calculate this estimate by using either the actual track duration of a song (if I own it) or a constant that is based on the average song length in my library (about 4 minutes).

4,449 of those minutes were on Spotify, 13,715 of them on SoundCloud.

What helps that difference along is that I purchased 1,091 songs in 2025 on iTunes and Bandcamp. A few more might have snuck in through Beatport as well, but

Bandcamp tracks auto-add a comment with a URL to the bandcamp page where the track was purchased, and tracks purchased from the iTunes store have explicit isPurchased metadata. As far as I can tell, no signifier is present in the metadata for tracks purchased from Beatport.

, so I can’t count them.

I also listened to some music live, but given the year I had, it’s perhaps not surprising that I only went to 5 concerts and DJ sets in 2025, and only went for the opener once. Recovering from major surgery is no joke (even though it was planned!), and I’m glad to be back on my feet and going to shows.

I listened to 7,968 songs (4,299 unique tracks) and 2,057 total artists, of which 700 were new to me.

Of course, because I don’t run a pristinely clean music metadata pipeline, muddled in those 700 “new” artists are a lot of artists I’ve already discovered. For example, some discovered artists are “Malugi & Wolters” or “BICEP, ELIZA” or “Diffrent | Boiler Room”. If my metadata were cleaner (more accurate), those artists wouldn’t be listed as new artists, because I discovered Malugi in 2024, Wolters in 2024, Bicep in 2017, and Diffrent in 2024.

Among those 700 “new” artists, though, there are some serious highlights that were actually new to me in 2025: Faster Horses, Djo, JADE, GLOCKTA, Joshua Idehen, and IN PARALLEL (it’s trendy to be all caps I guess).

That’s a high-level review of some high-level stats, but let’s get more granular. Who were my top artists of the year?

My “top artists” of 2025 #

Due to the disparity of listening volume in each place, my top artists look wildly different across the services…

| Spotify | SoundCloud | My Last.fm data |

|---|---|---|

| HAAi | Beyoncé | Chappell Roan |

| Bon Iver | Rinse FM | Carly Rae Jepsen |

| Joe Goddard | Fred again.. | Mk.gee |

| Sabrina Carpenter | Mk.gee | Waxahatchee |

| Upper90 | Tom VR | Tourist |

Much like last year, SoundCloud reveals a flaw in its metadata, ranking an online radio service as my second top artist of the year. Shoutout Rinse FM DJ sets!

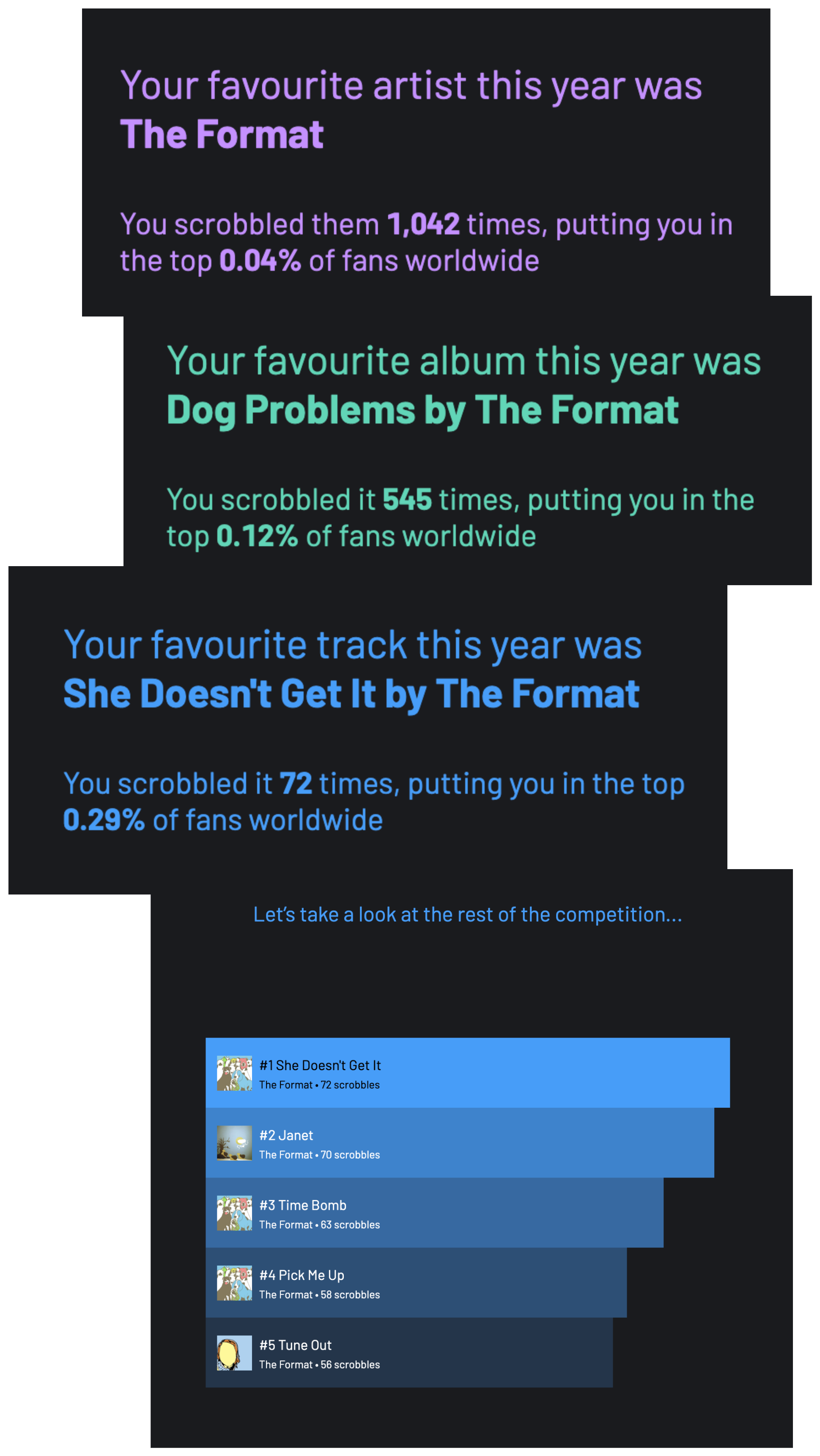

Comparing Last.fm to Last.fm? #

Because I’m writing this post later than usual, I can compare my Last.fm Last.year report with Last.fm stats that I pipe into a Splunk instance. My data pipeline pulling data from the Last.fm API isn’t perfect, so I was anticipating some minimal disparities, but I was very surprised:

| Last.fm Last.year | My Last.fm data |

|---|---|

| The Format | Chappell Roan |

| Carly Rae Jepsen | Carly Rae Jepsen |

| Mk.gee | Mk.gee |

| Chappell Roan | Waxahatchee |

| Waxahatchee | Tourist |

The Format dominated my report and was far-and-away the top artist of my year.

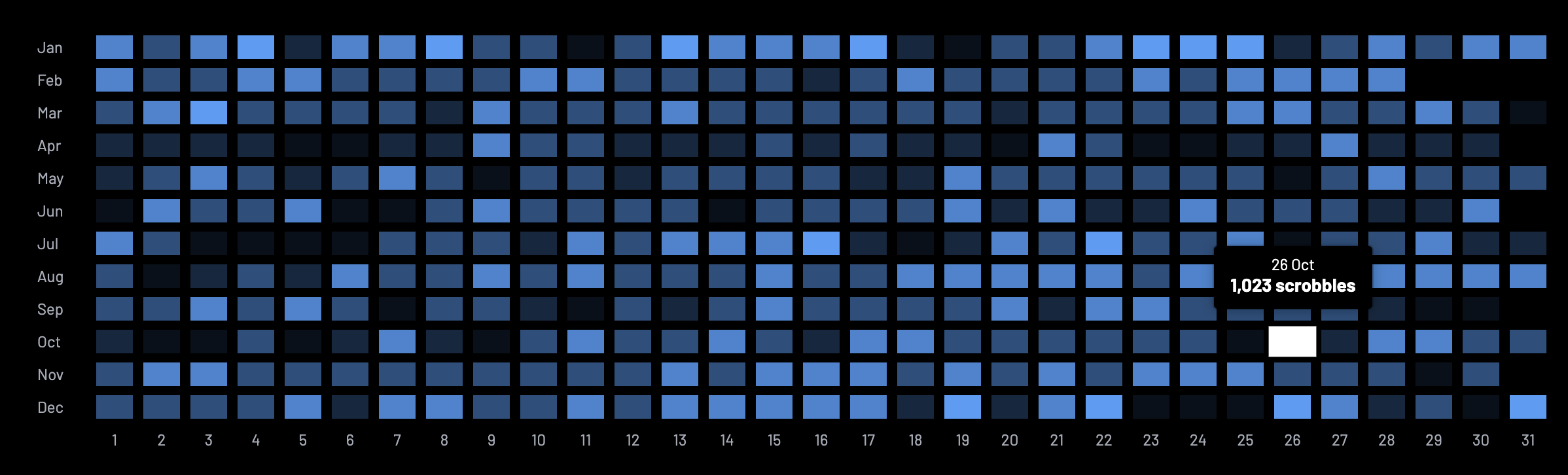

I was perplexed until I noticed this heat map visualization:

Somehow, the data tracking recorded 1,023 music listens (what Last.fm calls scrobbles) for that one day, October 26, 2025. Given that there are 1440 minutes in a day, I definitely slept that day, and the average length of a song in my library is almost 4 minutes, there’s a lot that points to a data error.

I thought maybe the excessive recorded listens was due to a time zone issue caused by some travel, but I didn’t travel on that day. Me being me, I dug deeper.

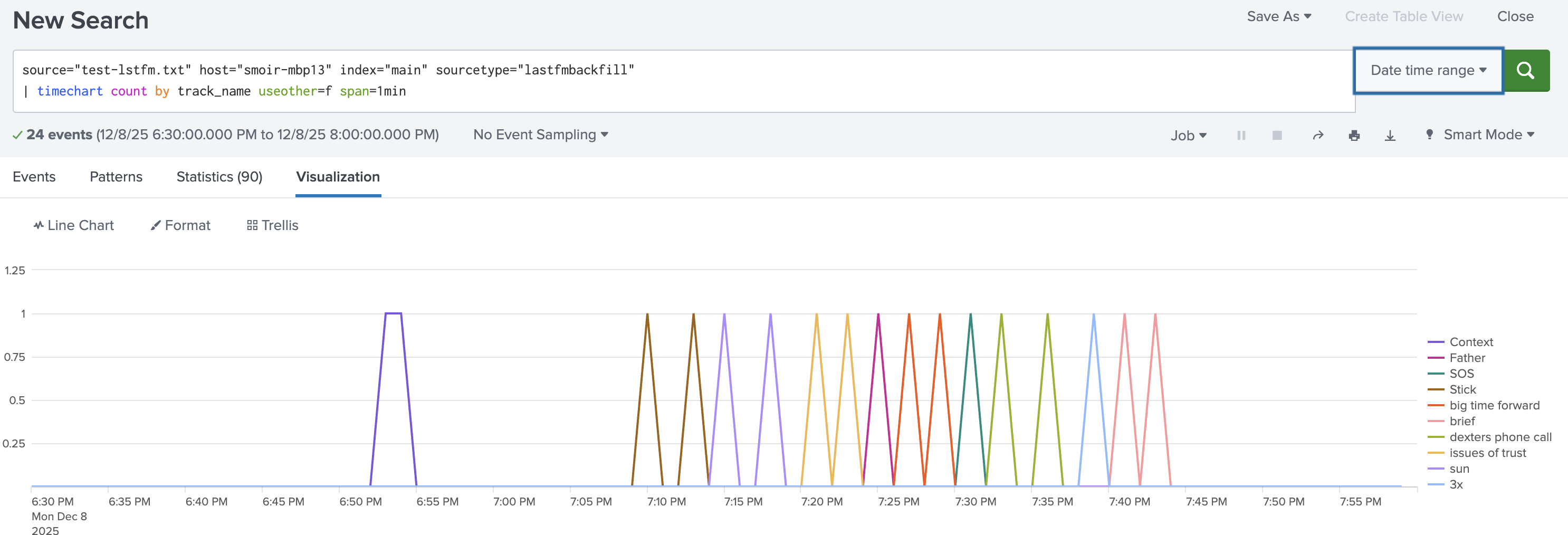

Visualizing the listening events for the day in question, the issue is obvious. Here’s what a On December 8, 2025, I listened to some tracks from Black British Music by Jim Legxacy. looks like as a line chart, plotted by minute:

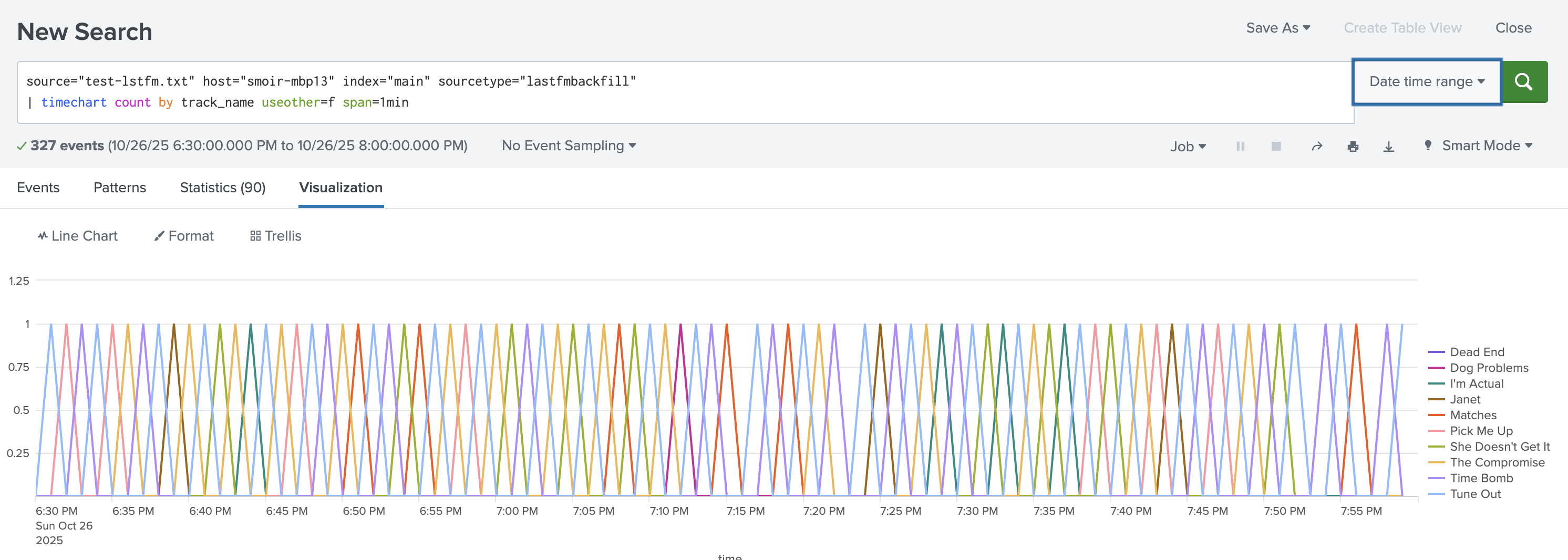

By contrast, here’s what my listening session looked like on October 26 as recorded in Last.fm:

There’s still 1 track being recorded at a given time, but despite the time bins only being one minute long in the line chart, the lines overlap.

Calculating the differences between events over time reveals that throughout the entire day, 52 events were separated by only 1 second from another event, 45 only 2 seconds, 44 events happened just 3 seconds apart from another event, on down the line:

It’s absurdly inaccurate. As one last example of the data issue, in my iTunes library I have The Format album Dog Problems, The Format album Interventions & Lullabies, and the Snails EP.

I painstakingly reviewed 971 rows of data to attempt to reconstruct a legitimate listening session using timestamps for each recorded listen and track duration. In this reconstruction, I assume that I listened to the tracks of their discography in my iTunes library once consecutively.

Here’s how that listening session looks in the data, where each row number corresponds to the event number out of that 971 event period that occurred over a few hours:

| Row number | Time | Track name | Album | Track number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18:49:24 | Matches | Dog Problems | 1 |

| 69 | 18:51:46 | I’m Actual | Dog Problems | 2 |

| 131 | 18:53:58 | Time Bomb | Dog Problems | 3 |

| 196 | 18:57:59 | She Doesn’t Get It | Dog Problems | 4 |

| 247 | 19:02:11 | Pick Me Up | Dog Problems | 5 |

| 294 | 19:04:33 | Dog Problems | Dog Problems | 6 |

| 333 | 19:08:57 | Oceans | Dog Problems | 7 |

| 365 | 19:14:42 | Dead End | Dog Problems | 8 |

| 389 | 19:18:27 | Snails | Dog Problems | 9 |

| 430 | 19:21:28 | The Compromise | Dog Problems | 10 |

| 459 | 19:34:01 | Inches & Failing | Dog Problems | 11 |

| 489 | 19:37:33 | If Work Permits | Dog Problems | 12 |

| 517 | 21:16:47 | The First Single (Cause A Scene) | Interventions & Lullabies | 1 |

| 527 | 19:46:43 | Wait, Wait, Wait | Interventions & Lullabies | 2 |

| 569 | 19:51:05 | Give It Up | Interventions & Lullabies | 3 |

| 594 | 20:00:58 | Tie the Rope | Interventions & Lullabies | 4 |

| 648 | 20:02:49 | Tune Out | Interventions & Lullabies | 5 |

| 671 | 20:09:29 | I’m Ready, I Am | Interventions & Lullabies | 6 |

| 700 | 20:11:30 | Sore Thumb | Interventions & Lullabies | 8 |

| 728 | 20:28:18 | A Mess to Be Made | Interventions & Lullabies | 9 |

| 756 | 20:31:28 | Let’s Make This Moment a Crime | Interventions & Lullabies | 10 |

| 789 | 20:35:50 | Career Day | Interventions & Lullabies | 11 |

| 803 | 20:43:12 | A Save Situation | Interventions & Lullabies | 12 |

| 880 | 20:44:59 | Janet | Snails EP | 1 |

| 907 | 21:30:17 | Wait Wait Wait (Acoustic) | Snails EP | 2 |

| 925 | 21:45:18 | Tune Out (Acoustic) | Snails EP | 3 |

| 949 | 21:50:27 | On Your Porch (Acoustic) | Snails EP | 4 |

I italicized The First Single (Cause A Scene) because it is the only instance of that track in the listening history, but it didn’t match up with the listening session I reconstructed.

Buried in this dataset is 68 total recorded listens of the song Janet, and 69 of the track She Doesn’t Get It, ostensibly all in the same 6-hour time span. They’re both excellent tracks, and I’m a big fan of the Format, but their music isn’t good enough to transcend space and time.

They did announce a new album in 2025, and a tour that (finally) replaces their tour originally scheduled for 2020, which is why I was listening to them.

As for the cause of the data anomaly? My only and best guess is that I might have been trying to listen to the tracks on two of my Sonos speakers, and either the app or something about the Airplay connection tripped up the Scrobbles for Last.fm app.

Flukes with data collection can lead to frustrating outliers that can skew an annual analysis of quantitative music listening data, but other flaws are inherent in the form itself.

Flaws of an annual quantitative data review #

Quantitative listening data prioritizes volume of listens over time, and a year is a somewhat arbitrary boundary when music discovery happens year round.

For an artist to show up in an end-of-year top 5 ranking based on total listen count, a few things bias an artist toward inclusion:

- Early discovery — An artist discovered in January is more likely to have more listens than one discovered in November, making it more likely to be a “top artist” of the year.

- Large discography — If an artist has a lot of tracks released, it’s easier to listen to a lot of music by that artist (because there’s a lot to listen to!)

- Intent — It’s difficult to listen to an artist a lot by accident, so there usually needs to be some sort of intent, whether it’s to check out the latest album by an artist (and then realize you zoned out, so you put it on again), listen to the back catalog of an artist you just discovered, or put on something familiar while you’re working.

What you spend a lot of time listening to, though, isn’t necessarily what you most enjoyed listening to, or what had an emotional or other impact. It’s easier to listen to things and forget about them and drift into the sameness, and then that artist shows up on your most-listened-to list at the end of the year because you put their discography on while you completed an all-day task.

Often, the songs I most enjoy listening to are the ones where, when they come on, I mentally picture myself at a club dancing to them, or sing along to them in my head, or pull them up so that I remember what the track is so that I can recommend it to a few friends later. They’re the ones that make me sit up and take notice.

That isn’t to say that the artists I listen to in the background aren’t good, or that I don’t enjoy them — I have to, in order to listen to them that much. I need them to be good! But at the level of frequency of listens needed to break into the top 5 list for me, I’m really listening to them a lot.

The point I’m trying to make here is that frequency of listens can be a proxy for most enjoyed, but it is an imperfect proxy metric for an unclearly defined “objective function” of “best”. That’s why companies like Spotify choose “top”, because top is a clear statistical measure — given a metric, list the top 5 entries in the list.

My top albums of the year #

I’m not much of an album listener, but I’m learning! As such, here are my top albums of the year according to Spotify and Last.fm (SoundCloud’s “set” based format doesn’t lend itself that well to tracking albums):

| Spotify | My Last.fm data |

|---|---|

| Global Underground #46: ANNA by ANNA | Two Star & The Dream Police by Mk.Gee |

| Sunshine on Leith by the Proclaimers | Emotion (Deluxe Expanded Edition) by Carly Rae Jepsen |

| SABLE, fABLE by Bon Iver | Tigers Blood by Waxahatchee |

| Harmonics by Joe Goddard | The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess by Chappell Roan |

| Demos by orbit | Portrait of a Legend: 1951–1964 by Sam Cooke |

The Spotify albums are fascinating to me. Because of my low listening volume on that service in 2025, the list is a very odd cross-section of listening behavior:

- I have literally no recollection of listening to the album that Spotify claims was my top album of the year.

- The Proclaimers have some bangers, so I probably put that album on at work one day.

- SABLE, fABLE was released in 2025, so this was likely a case of album evaluation while trying to decide whether to purchase it.

- Harmonics I first discovered on Spotify after a friend of mine shared it as part of her end-of-year playlist for 2024.

- Similarly, Demos by orbit was shared with a friend of mine who was recommending it to me (but I wasn’t a fan, sorry!)

Meanwhile, my top albums of the year reflect some serious obsessions…

- Mk.gee was an early 2025 discovery, and the album is short and easy to listen to in terms of suitable moods and temperaments, so I put it on a lot in the early months of the year.

- It was the 10th anniversary of Carly Rae Jepsen’s EMOTION and it remains a no skips album. I reveled in the anniversary with some serious on-repeat binge listens.

- Tigers Blood reminded me that I can be an indie folk girlie when I feel like it. I ended up seeing Waxhatchee live in 2025 which helped me remember this album again later in the year.

- Chappell Roan remains a favorite (I cannot stop listening to her Bonnaroo set on YouTube) so while I’m a little surprised I listened enough for The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess to rank fourth on this list, I’m not that surprised.

- Portraits of a Legend: 1951 – 1964 is the Sam Cooke greatest hits album and I can’t recommend it enough.

Those were my most-listened-to albums of the year, but there’s basically no overlap with my personal favorite albums (and EPs) of 2025…

My favorite albums of the year #

The timing of some of these album releases would’ve made it impossible for them to chart as a “top” album of the year, and this is why it’s relevant to consider different personal metrics besides “top”.

-

I’m always here for a Tourist album, and when he promised a trance album I was sold. Classic Tourist but more high energy than usual (as one would expect from a trance album). There’s something about the familiar beats and grooves that earmark his tracks that make me happy and entrance me.

-

I didn’t realize how badly I needed this album until her single Can’t Stand to Lose came out, and then I was like oh this is going to be a peaceful, contemplative, gift. After Always Ascending came out a few years ago I am delighted that she collaborated with Jon Hopkins on this album.

-

Bicep’s CHROMA era is a bit crunchier than in the past, but it hit. 004 ROLA is maybe my favorite track off the album. Listening to a Bicep album, I can’t help but think of their live sets and how all-encompassing and absorbing it is. The energy of this live album evokes their live set, and I’m grateful for it.

-

Based on how much I listened to his album In Circles, I was excited for this album. It’s a bit softer in energy than In Circles, but still a solid album with a bunch of favorites.

-

This list was originally 5 albums long, because Daphni = Butterfly was just good enough to make this list, and then I realized it doesn’t actually fully release until February. 2026 favorite albums list, here I come.

A couple honorable mentions are Skin on Skin = Home is True and Marlon Hoffstadt = All Yours.

Two albums I discovered in the last few weeks also deserve honorable mentions, Djo = The Crux and Jim Legxacy = black british music (2025).

Very different albums, but both are great listens straight through. Jim Legxacy had a song recommended on the Said the Gramophone list for 2025, then I listened to the whole album and was sold. It’s firmly a no skips album.

I thought I discovered Djo and his album The Crux through the Said the Gramophone list too, but after some sleuthing I realized that it must have come from listening to my SoundCloud Playback playlist, which had a bunch of Mk.gee tracks on it. The autoplay after that playlist ended included some Djo tracks, which were so good I dug deeper and here we are. (the same or similar autoplay session led me to discover Florence Road’s track Goodnight, which is a banger)

Favorite EPs of the year #

EPs sit in a weird spot. Too long to be a proper single, too short to be an album (although a 7 track album also feels too short to be an album!), I still want to recognize the progression toward a form. Here are my favorites of 2025:

-

Effy crushes this EP with 3 straight bangers. One of the best in the game atm.

-

DJ HEARTSTRING & SWIM = FOREVER

Another collaboration between two favorites with a really solid set of songs. Hard to go wrong, especially when the opening track was one I’d been wanting to pick up ever since I heard it in a DJ set.

-

Upper90 & Baron von Trax = At Night EP

They themselves call it an EP but it’s only two tracks! But both are bangers, and it’s only fair for Upper90 to make an appearance in a list of my favorites of the year.

-

Another two-track EP (is it a single at that rate? who even knows with digital releases), both tracks hit hard but Need Right is my favorite to listen to. Dogma is maybe spookier.

-

Something about this EP feels almost retro? Like it didn’t come out in 2025? I can’t really explain it, but Desire To Stay is my favorite track here.

-

The best track is Here, but Essa is a close second. The driving background sounds, Cameo Blush is another producer with some signature sounds.

I made up for the list of 4 favorite albums with a list of 6 favorite EPs. I think it’s also telling that the list of favorite EPs is primarily the newer producers on the scene, still finding their sound and crafting their own tracks, whereas the electronic artists on the favorite albums list have been around the block a bit.

My top songs of the year #

According to each service that I use to listen to music, and about which I also have quantitative listening behavior data, my top 5 songs of 2025 were as follows:

| Spotify | SoundCloud | My Last.fm data |

|---|---|---|

| Simon & Garfunkel - [Cecilia]2 | Upper90 at Intercell Indoor 2024 | Paravi - Angry |

| HAAi - Can’t Stand To Lose | Upper90 at Glitch Berlin | Faster Horses - Wish U Were Mine <3 |

| The Proclaimers - Then I Met You | Jacques Greene 11th January Rinse FM | KH - HandsToMyself |

| Joe Goddard - New World (Flow) | LFE-KLUB Mix w/ Upper90 | Mk.gee - Alesis |

| Nina Sky - Move Ya Body | SWU FM: t e s t p r e s s and Baron Von Trax | HAAi - Can’t Stand To Lose |

I listened to Cecilia 5 times, which was enough for Spotify to call it my top song of the year.

SoundCloud being SoundCloud, all of my top 5 songs of the year were hour+ long DJ sets, with the Upper90 set from Intercell Indoor 2024 remaining a favorite for focus time at work and a plethora of IDs:

It’s not surprising that HAAi’s track Can’t Stand to Lose made it onto multiple lists. I’d been eagerly awaiting her album and it was the first single released, and therefore had the most opportunity to be listened to repeatedly.

Most of the songs on my Last.fm list either resonated with me at particular moments, or made it onto my quarterly playlists consistently — HandsToMyself was on 3 out of 4 of the quarterly playlists I used as my default listening playlists throughout the year.

The playlist as codifier #

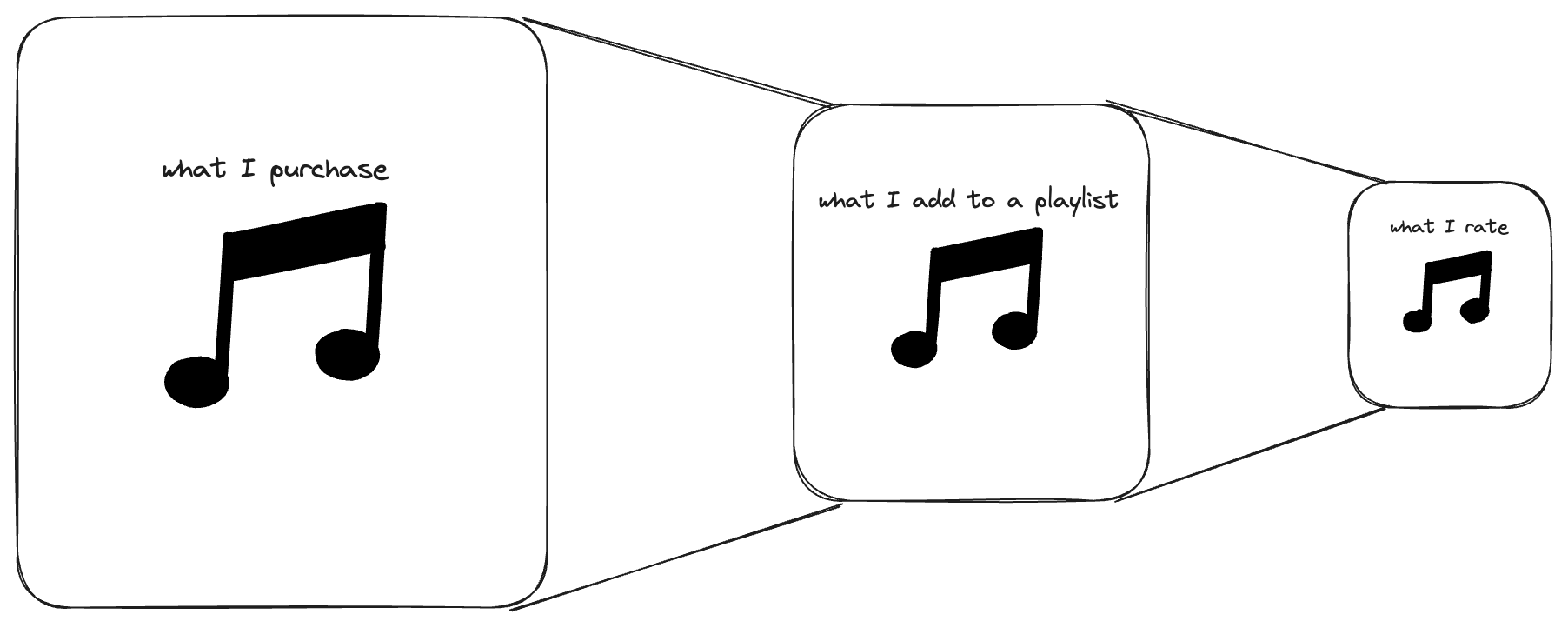

What I spend the most time listening to are whichever songs I put on my quarterly playlists. For the most part I’m mindlessly putting on a playlist for my morning commute, so as I buy music it has to make it through the funnel.

There are certainly some artists and albums that I discovered or even purchased music from in 2025 that are great but which I didn’t listen to that much. Looking at my library, Mild Minds’ album GEMINI comes to mind, as does SHERELLE’s WITH A VENGEANCE or BAMBII’s INFINITY CLUB II.

For the artists and albums that didn’t make it to purchase, or didn’t make it to a playlist, the sound might not have found me at the right time or mood, or I was simply too busy to spend time with the music after buying it, and never went back when I did have time.

For some tracks, I liked it enough to buy it but then forgot entirely about it.

Because my rating system requires some input from me — either taking the three-tap step on mobile to rate a track, favorite it, or add it to my quarterly playlist — it can be easy for me to forget that I like a particular artist or track if I don’t take action to record it.

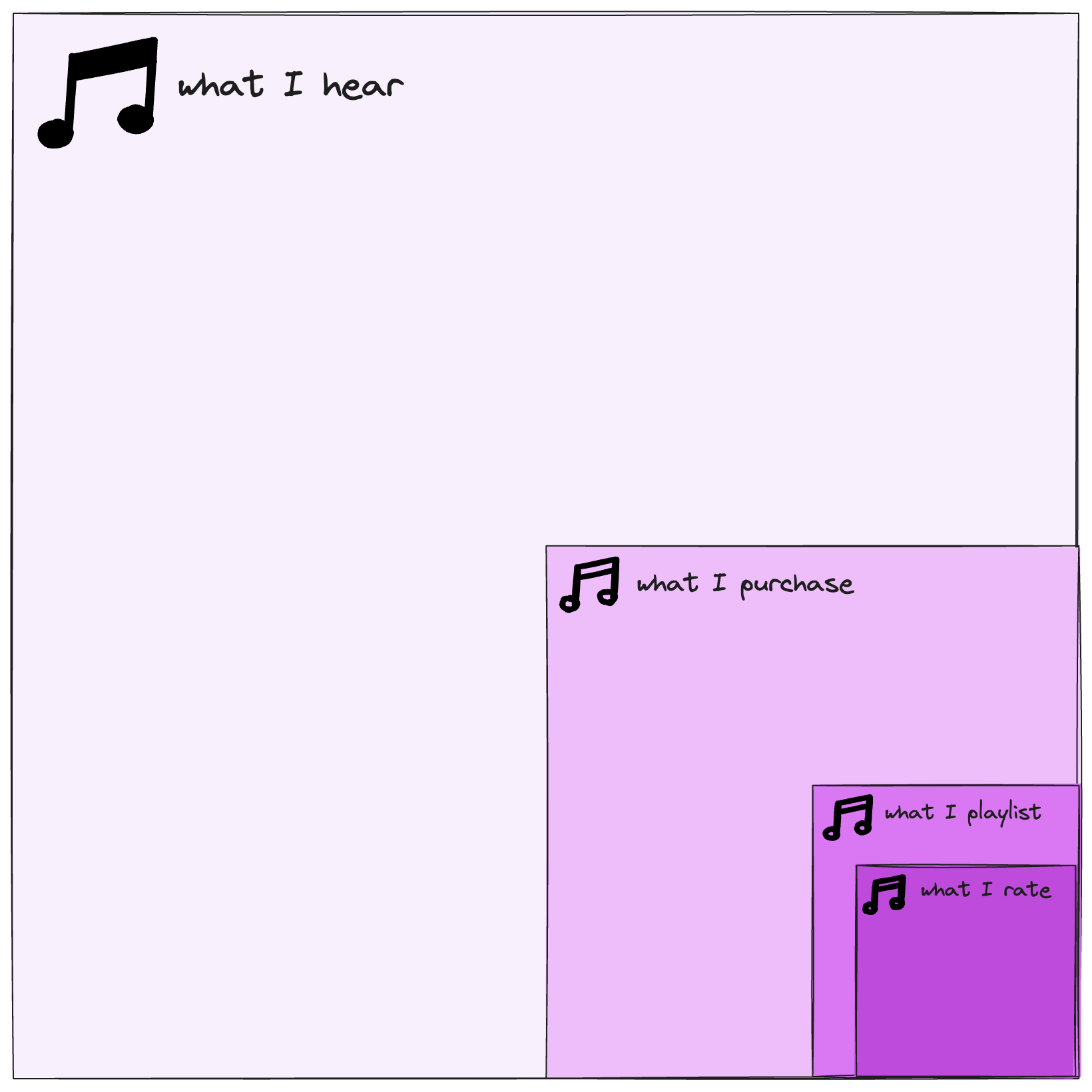

Overall, I listened to 4299 unique songs (and sets) in 2025, purchased 1091 songs, added 309 of those songs to my quarterly playlists, and rated 213 songs.

To visually capture the difference in quantity throughout those different steps, I made this to-scale but pseudo treemap chart by hand:

If a song makes it through to a playlist, odds are that it will stick around and end up on one of these year-end lists!

My top songs of 2025 are all good songs (or sets, as the case may be), but my favorites of the year were much tougher to narrow down.

Favorite tracks of the year #

I had 30 favorite tracks of 2025, but I want to talk about 5 that were particularly meaningful, memorable, and enjoyable tracks for me…

-

Sam Cooke - (What A) Wonderful World

I listen to a podcast called Hit Parade and he had a couple episodes on Sam Cooke, Don’t Know Much About History that I listened to while I was recovering from surgery. I was familiar with his songs You Send Me and Bring it On Home to Me, but hadn’t explored his back catalog. And boy what a history, what a performer, and more. This track is my favorite of the new-to-me tracks, but I recommend the full greatest hits and beyond. I also listened to all of this when I was doing some research into the background of Motown Records, and it was a nice confluence to learn a lot about another soul legend.

-

From the artist that made “Mum Does The Washing” which featured on 2024’s Said the Gramophone list, this caught my attention immediately with its upbeat and hopeful mantras. The album title also hits: “I know you’re hurting, everyone is hurting, everyone is trying, you have got to try.”

-

Too $hort - Blow the Whistle (black panda x seanathan remix)

This track is the far and away standout of an 80+ track compilation of bootlegs that has changed the way I hear this song. I can never hear the original again, it’s too slow and ruined for me. A good bootleg/remix is transformational like that.

-

ec2a put out this EP and as a label that has released Soul Mass Transit System, Silva Bumpa, and Club Angel, I try to listen to the releases by artists I don’t recognize when I have the capacity. This track caught my attention immediately and it still has me in its clutches. Some energy from idk, is it drill? Is it something else rap-adjacent? Idk genres anymore but the insistent rhythmic vocals are basically another instrument that keep me moving.

This song has <1000 streams on Spotify, so if you use that service maybe try to drive it up a bit so Glockta gets some royalty cuts? (Or buy it on Bandcamp so they get paid for real).

-

The Shapeshifters - lolas theme (Luxusvilla edit)

This is the sort of track that I could only discover organically — I first heard this in a trance DJ set (Upper90? Marlon Hoffstadt? It’s lost to me now) but I went down the pathway of digging through comments and trying to find the ID, then trying to find a way to purchase the track. Like most tracks of this length, it takes a bit to get going (probably because it’s meant to be played out, and not at home) but give it a minute (or skip ahead) and it will start to hit.

Even in attempting to rank this list, I couldn’t decide on one definition of “best”. Because I listen to different tracks for different reasons, to fit different purposes, different moods, tasks, and energies, there can be no one best song.

A lot of my favorite tracks of 2025 are high quality tracks from artists that I’ve enjoyed for several years now:

- Aloka - Stay On Track

- salute - gbesoke (feat. Peter Xan)

- Bushbaby & ELOQ - Breaka Breaka

- DJ BORING & SWIM - Stay With Me

- Interplanetary Criminal - Slow Burner

- NOTION - BE YOUR GIRL DUB

- Faster Horses - Wish U Were Mine <3

- LB aka Labat - Double Happiness

- Diffrent - Piece of My Soul

- Y U QT x Bullet Tooth - Technique ft Flydat

Others were new-to-me artists or tracks that I discovered from DJ sets:

- REESE - Where Have You Been Dub

- Sam Alfred - Feel the Friction

- KI/KI & Marlon Hoffstadt - Losing Control

- Pegassi - No Go Zone (Pegassi Remix)

- Sudoo - Out My System,

Still more favorites were more organic discoveries from researching upcoming shows happening in the city: Funk Tribu - I Got it For You, or a record label that I follow: Field Motion - Deflate Me.

It’s somewhat chaotic to listen to all of these tracks together (I am primarily still a playlist listener, so I do). A lot can happen in a year and a favorites ranking must also be similarly diverse.

Beyond top artists, top albums, and top songs, Spotify and SoundCloud shared some other information in their 2025 wrap-up posts…

What is Spotify Wrapped for? #

In addition to top songs, top artists, and top albums, Spotify usually includes other bits of information that it packages up in an effort to share ~ * insights * ~ about your music listening.

In my opinion, the 2025 Spotify Wrapped really exposed how the company thinks of the users of the Spotify service as consumers of Spotify rather than music.

The excess insights beyond the top songs, artists, albums, and genres focused on your behavior on Spotify used as a proxy for your music listening habits. When you don’t use Spotify much, this perspective falls flat and reveals itself as a transparent skin over the internal advertising-relevant user clusters that Spotify maintains about its users.

For example, let’s dig into the “clubs” and the “listening age” that supplemented the standard list of top artists, songs, and genres in 2025.

Why didn’t the “clubs” land? #

In 2025, Spotify Wrapped included some “clubs” that Spotify grouped everyone into. Among the folks I follow online and the online communities I’m part of, I think maybe one person shared their club membership out of dozens that were sharing their Spotify Wrapped stats generally.

So why didn’t the clubs resonate with people? Why did basically no one share their club membership and “role”?

In my opinion, it’s because they were boring and impersonal. There was nothing inspiring or revealing about the club definitions (or your assigned role within a club) — no insights to be gained about yourself. Nothing about the club or membership evoked a sense of personal identity.

I want to explain more about why by digging into the club and role definitions.

According to a Spotify blog post “Join Your Wrapped Club”, published December 7, 2025, the clubs were:

| Club | Description |

|---|---|

| Cloud State Society | Your club finds peace through music. New members are gifted house plants. |

| Grit Collective | Your club believes in rebellion through music. There is no club rulebook. |

| Club Serotonin | Your club thrives on good vibes. Members insist on natural lighting. |

| Full Charge Crew | Your club is committed to the endless party. Club events are high energy, zero chill. |

| Cosmic Stereo Club | Your club traverses terrestrial barriers with music. Clubhouse seating is entirely bean bags. |

| Soft Hearts Club | Your club believes that vulnerability is the key to great music. Its doors are always open. |

Within each club, Spotify users were also assigned roles that they played within each club:

| Role | Description |

|---|---|

| Leader | Your listening is strongly aligned with club values, making you a perfect role model. |

| Scout | You listen to the freshest releases, always pushing your club forward. |

| Archivist | Your listening delves into past eras, ensuring club history never fades. |

| Curator | You’re a focused playlist creator, combining the best of your club into mixes. |

| Collector | You often save music to your library, building a large club collection. |

| Recruiter | You share music far and wide, bringing in frequent new club members. |

| Loyalist | You rarely skip tracks, confirming your unwavering dedication to the club. |

| Supporter | Your listening favors one artist, ensuring they’re heard around your club. |

| Broadcaster | You listen to podcasts more than others, keeping club conversation alive. |

| Specialist | You explore experimental sounds, refining your club’s sonic boundaries. |

What does it all mean?! It’s a lot of word salad without a lot that resonates.

My club was the “Full Charge Crew”, which as described basically says “you listened to a lot of high energy music”. Okay! I did do that. Is the high energy music part of my personal identity? Does it reflect my friend group? (Spotify doesn’t know, becuase it isn’t a social network (although they did I was fairly bullish on Spotify’s collaborative interactions and messaging functionality when I was writing about music discovery patterns back in 2019, but Spotify previously removed messaging back in 2017, and I wrote about that in my music discovery blog post last year. ).)

Instead, my club assignment directly reflects a cluster that Spotify’s machine learning algorithms grouped me into based on my user behavior data collected while I used the service.

As outlined by Spotify in the same blog post:

Your Club captures the emotional qualities of your year in music. That includes the moods, genres, and musical terms that defined what you listened to most.

Each track is tagged with descriptors. Take your favorite breakup anthem, for example. It might be tagged with descriptors such as “heartbreak” and “yearning” because of the titles of the user playlists that it appears on.

These descriptors roll up into six possible Clubs. For each one, we calculate a score based on streams and assign you to the Club with the highest score.

Your role in a Club is determined by your standout on-platform behavior and listening compared to the rest of your Club.

To restate it more technically: Spotify collects cultural metadata about tracks (such as from the titles of playlists that you and others create on the platform). To define the clubs, Spotify grouped the metadata into 6 clusters based on the descriptors. My club (Full Charge Crew), for example, probably had a number of tags like “energy” or “high energy” or “no chill party”.

When each user’s listening patterns were analyzed, the tracks they listened to were scored according to which cluster the tracks belonged to, and the cluster in which you streamed the most songs defined your club. Club is a good name for it, representing both a group of people, and a place you might go to listen to music.

Role assignment, meanwhile, is defined in relation to the club, which means that your role reflects your user behavior on Spotify in relation to the aggregate user behavior patterns of the other users grouped into your club (not your friends, but mysterious strangers that listen like you).

These roles transparently reveal: “This is how you used Spotify in 2025”. The roles and clubs are cold, impersonal, and expose the volume of user data that Spotify collects about its users—primarily to sell ads, but also to fund the development of royalty-free or low-royalty content.

In my opinion, the roles can be basically summarized as:

| Role | Honest description |

|---|---|

| Leader | You listened to music that was mostly the same as other people in your cluster. Good for you! It might be boring, but we’ll call you a leader for doing what everyone else did. |

| Scout | You listened to new music when it came out. Thanks for that. |

| Archivist | You listen to music that is older (what the industry calls catalog music, or music released more than 18 months ago). That’s cool. |

| Curator | You make playlists. Who knows why you make playlists, or what of, or who for, but that’s what we know about you — you make playlists. |

| Collector | You save music to your library. That’s all we know. You hit that <3 button that we changed into a + button that means different things in different places in the app! |

| Recruiter | You share music. Click that share button, copy those links. Thanks for sending people to Spotify, you’re recruiting people to our service and driving traffic. |

| Loyalist | You don’t hit skip very often. This is the most interesting thing that we could identify about your listening behavior. Maybe you listen on a smart speaker, or you work at a gym or a coffee shop that is (grayly) using your Spotify account to play music during the day. Either way, thanks for being Loyal to Spotify. |

| Supporter | You mostly listen to one artist. How INTERESTING. |

| Broadcaster | You listen to podcasts more often than other people in the cluster that we arbitrarily grouped you into. This probably means we can sell you more ads, or more specific ads because we have more content available about your interests as a result. |

| Specialist | You explore “experimental sounds”, which is undefined and seemingly meaningless, but it also makes you a “specialist” but a specialist in… exploration, I guess? |

The entire construct focuses on defining you by your behavior inside of Spotify, instead of your engagement with the music itself. Even the roles that are specific to music are defined in contrast to the behavior of other aggregate users in your cluster (sorry, club).

In the past, Spotify has grouped users into clusters as part of Wrapped. Most notably in 2023, identifying streaming habits based on how you use the service, but still framing the content in the context of you — making it more personal that you listen to music on shuffle or full albums or more. The streaming habit is positioned in contrast to other Spotify users.

Meanwhile, the clubs and roles identify other Spotify users and places you with them — assigning you a club and a role that you play in that club that you unwittingly attended by using Spotify.

In 2024, the “music evolution” was fully centered around you and your music listening habits, again drawing aggressively from the cultural metadata about music that Spotify collects, and in 2022 the focus was on a listening personality and an audio day — again, highly personal. Before 2022, Spotify shared more of its music metadata than user behavior data necessarily, focusing on an “audio aura” in 2021.

Instead of revealing anything insightful about how you interact with music, or what you listened to, your club and your role are about how you used Spotify, and what the streaming service is to you. But a club and role assignment wasn’t the only “nonstandard” information Spotify shared—they also assigned users a “listening age”.

What is a listening age, and why did it land with users? #

In contrast to clubs, listening age really landed. Most of my friends that shared a Spotify Wrapped post shared their listening age — some people only shared their listening age!

Something about the listening age made it well-suited for the type of virality historically associated with Spotify Wrapped:

- It’s somewhat inscrutable. What does it even mean?!

- It’s amusing to be told that your age is different than it is (sometimes wildly)

If there’s anything social media has taught us, it’s that dissonance is viral. Agreement doesn’t trend, sameness isn’t attention-grabbing. A listening age that is distant from the actual age of the person consuming the music is perfect for the algorithmically defined internet — the statistic is exceptionally shareable.

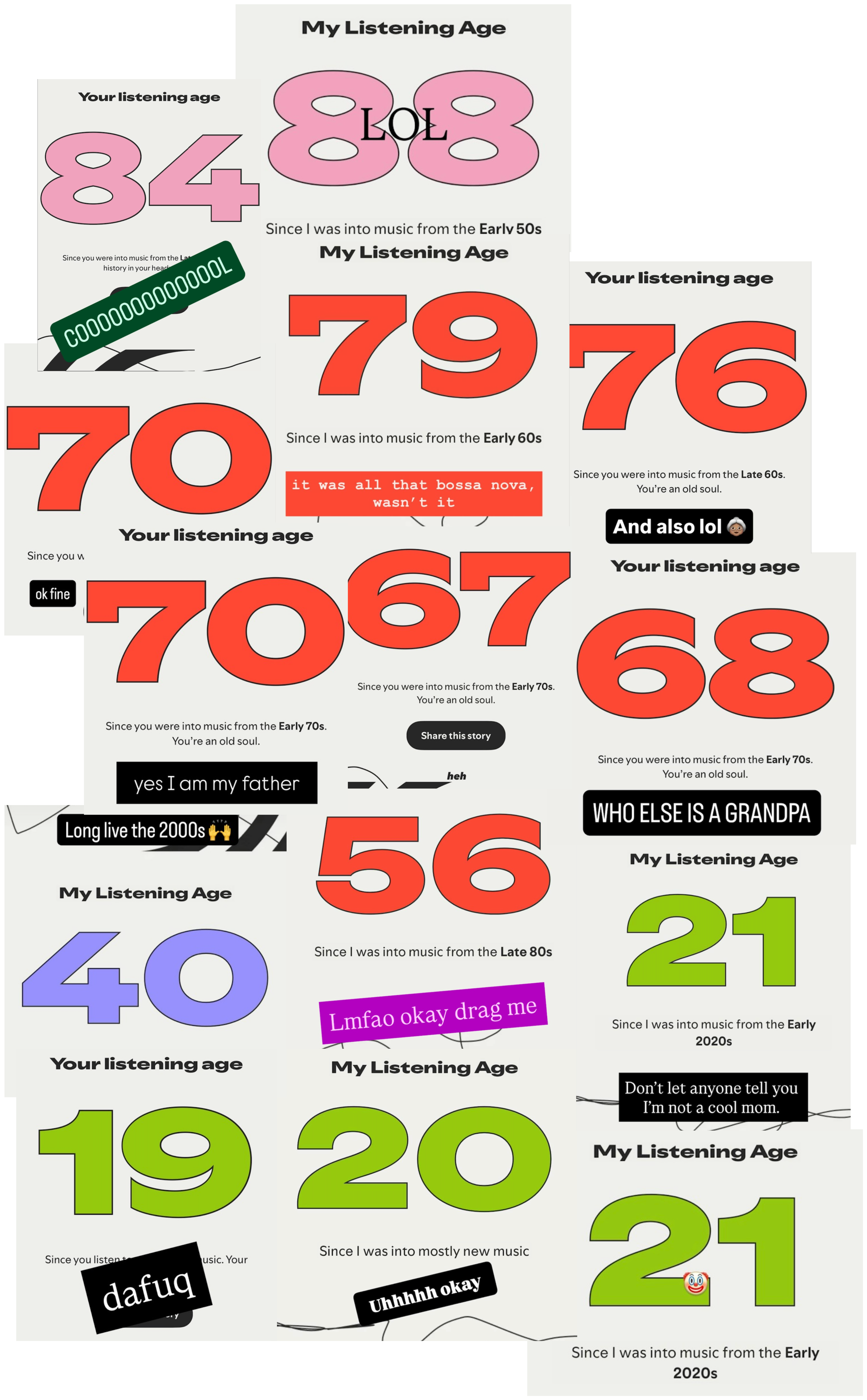

Some key examples that came across my feeds:

- A friend in her 50s and another friend in her late 40s — both with teenage listening ages.

- Another friend in her late 40s and another in her mid 30s — both early 20s listening ages.

- One friend in her mid-30s? A listening age in the mid-50s.

- More friends in their mid-30s had listening ages in the mid-70s and later, up to age 84.

So how was it calculated? According to Spotify in “2025 Wrapped: The Simple Truth About How Your Wrapped Comes to Life”

Your Listening Age is based on the idea of a “reminiscence bump,” which is the tendency to feel most connected to the music from your younger years.

First, we look at the release dates of all of the songs you played this year.

Next, we identify the five-year span of music that you engaged with more than other listeners your age.

We’re hypothesizing that this five-year span matches your “reminiscence bump,” assuming you were between 16 and 21 years old when those tracks were released.

For example, if you listen to way more music from the late 1970s than others your age, we playfully hypothesize that your “listening” age is 63 today, the age of someone who would have been in their formative years in the late 1970s.

To receive listening age, we needed a reported date of birth in your account of 1925 or more recent, plus 5 streams within a 5-year release date band.

Similar to the clubs, Spotify is again exposing the clusters that they use to group users — in this case, clusters by age, and comparing your behavior against that of others your age.

Spotify knows your real age, so it is indeed a “playful hypothesis” that the “five-year span of music that you engaged with more than other listeners your age” (emphasis added) is a time period that you’re reminiscing about, instead of one that you dove deep into one afternoon (or for several afternoons).

In my case, I listened to a good amount of Sam Cooke on Spotify before purchasing his greatest hits album. Sam Cooke’s song (What a) Wonderful World was released in 1960, my listening age was 78 — because if I was 17 in 1960 (and thus in peak “reminiscence age”), I would be 78 in 2025.

This graphic from Instagram account @_sportsball helps capture the math in chart form, comparing the number of songs that you listened to for a specific year in the yellow bars and the average number of songs from that year listened to by others in your age cluster as the green dots.

The computation of listening age might be playful, but it reinforces the notion that your music taste is set in your teenage years, and that you spend the rest of your life listening to the same music that you did as a teenager, reminiscing about those “brain-shifting listening experiences” that you no longer have.

And Spotify can profit off of this notion. If you are a passive, lean-back music listener, accepting the content that Spotify dishes up to you in the form of algorithmically curated playlists, Spotify can identify what music was popular during your “reminiscence age”, collect & contract a large amount of “perfect fit” content that requires paying low or no royalties, and direct your attention toward that. There is more profit in providing you more of what you might reminisce about than there is in driving true discovery.

What about SoundCloud Playback? #

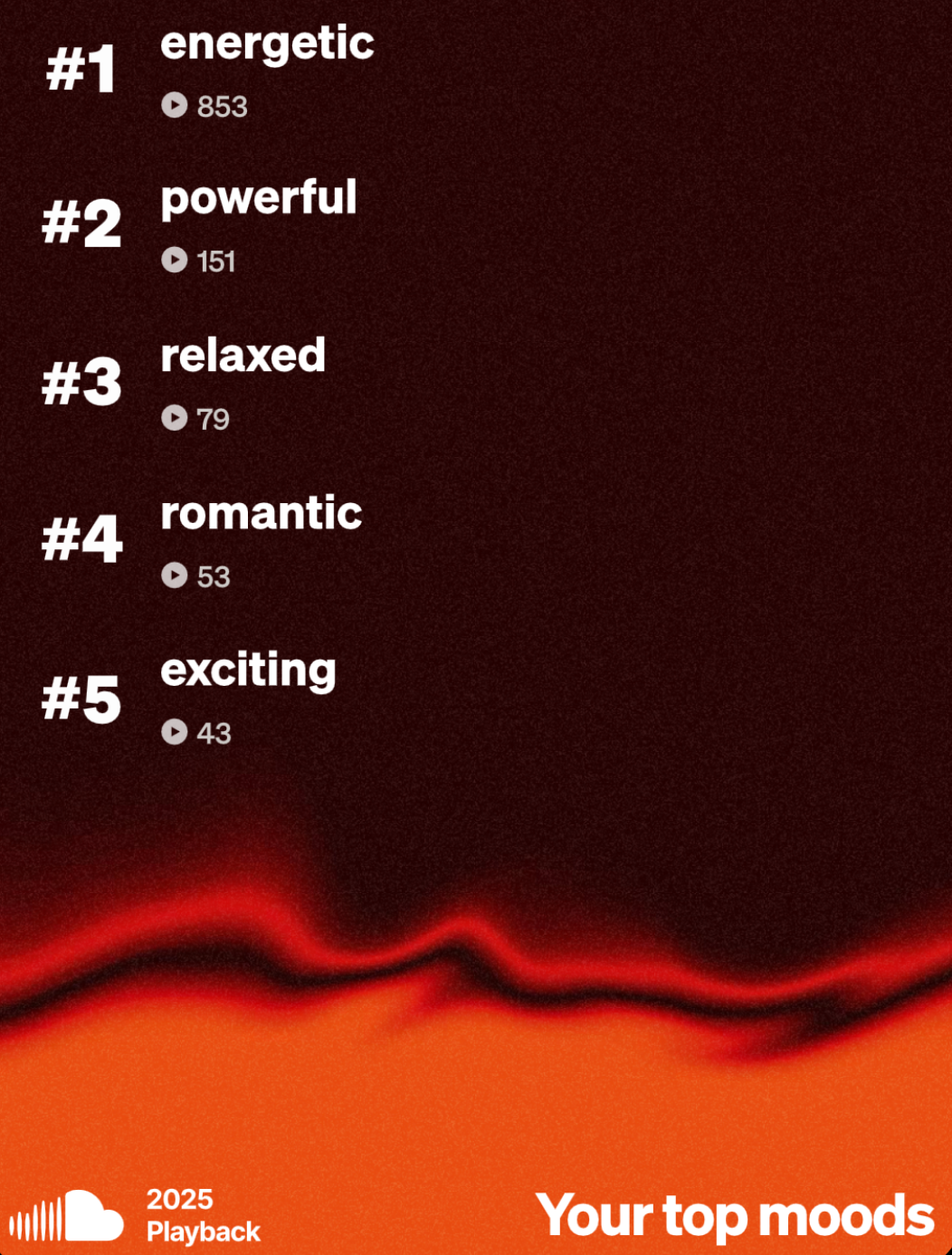

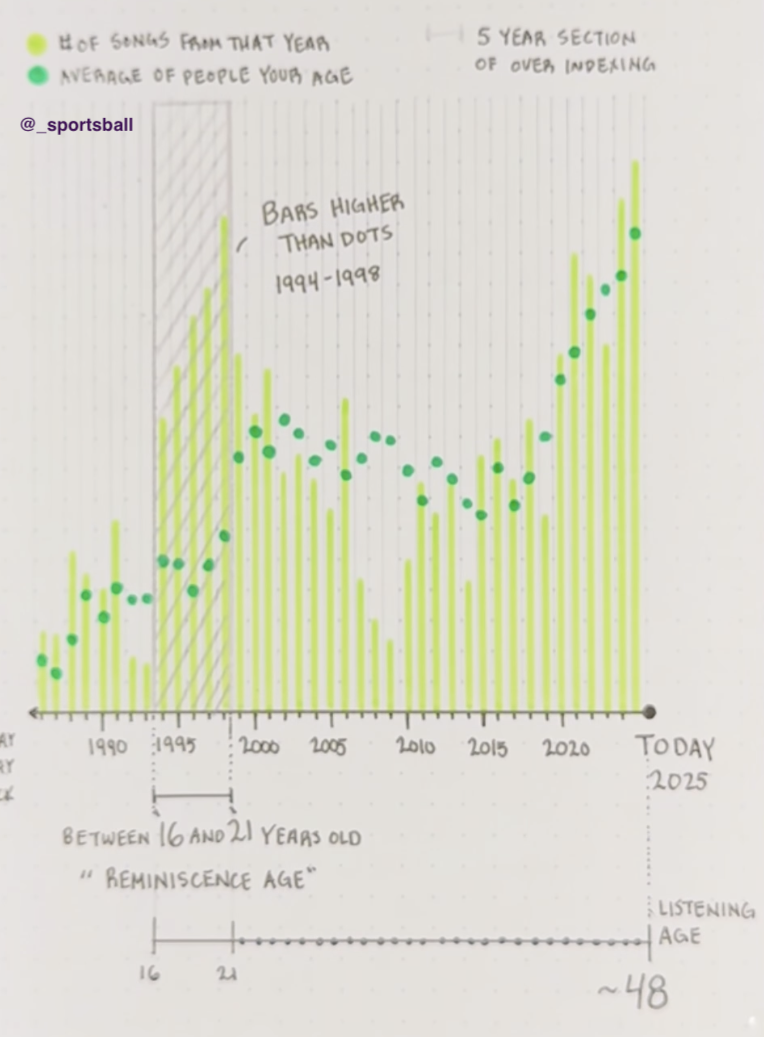

Spotify isn’t the only music service that I use, and SoundCloud also provides a list of top 5 metadata moments of the year. In addition to top artists, songs, and genres, in 2025, SoundCloud shared “top moods”.

For the first time, SoundCloud is exposing more of its slippery cultural metadata. SoundCloud has different opportunities to collect metadata than Spotify does — you can comment on individual tracks, even at specific timestamps—in addition to naming sets (playlists), which is the primary source of on-service cultural metadata at Spotify.

What amused me about my top moods is that in an effort to list 5 for consistency, it listed values that were wildly off scale from each other:

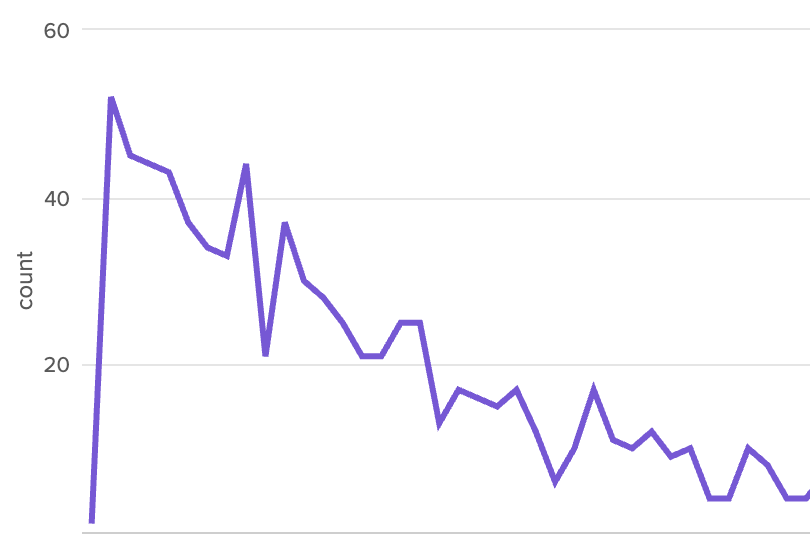

Or to graph those listen volumes (presumably that’s what those numbers are):

At that point, just tell me I had a high energy year in music and call it a day.

I am grateful for this peek behind the metadata curtain, however. SoundCloud doesn’t have nearly as many patents surrounding their music metadata collection, management, and usage as Spotify does (to my chagrin), which is one of the reasons that most of my metadata deep dives have focused on Spotify’s creation and management of it (I also focus on Spotify because they have so much of it).

In addition to far fewer patents, SoundCloud also I have a blog post draft I haven’t touched in almost 6 years that focuses on what the API endpoints that a company makes available says about the company and how they think about their product on the market—which customers are they targeting? What does the company expect the consumers of their APIs to do with the data they provide? It’s an insightful exercise to consider Spotify and SoundCloud at different poles of this market. .

While I haven’t dug into SoundCloud’s metadata culture as extensively as that of Spotify’s, I did listen to a HonestQuo Ventures podcast interview with Hazel Savage, their former VP of Music Intelligence and cofounder of (acquired) startup Musiio, which provides automated music metadata tagging.

Given all the investment and clear instances of cultural metadata present on their platform, it’s somewhat sad that we only see “moods” and “genres” revealed in the SoundCloud Playback. Perhaps there will be more peeks behind the curtain in the future—or I’ll just have to resign myself to the fact that SoundCloud is focusing more efforts on using the metadata to inform a superior recommendation algorithm rather than a copycat marketing stunt.

What exists beyond the streaming picture? #

If I consider the picture that Spotify Wrapped paints about my year in music, it looks something like this:

It’s kind of cramped, not very aesthetic, and is unbalanced.

If I add my SoundCloud playback to the equation, it might look more like this…

The SoundCloud picture on its own is more pleasing to experience, but is cramped and lacks a point of focus and visual interest. It’s a rather incomplete picture, but it has more of a lens into the full picture.

The size of these boxes is non-representative, but rather metaphorical. And what isn’t captured in this figure is how it felt to be sitting at that alpine lake, relaxing on a rock with my partner and enjoying the fact that I had managed to do the hike at all just a few months after having surgery. That feeling is part of why I write these aggressively long posts — to reflect and remember how the music I listened to in 2025 made me feel, not just what it was.

What music discovery means to me #

I listened to a lot of music in 2025 because it was familiar and let me focus on my work (my top “songs” of 2025 according to SoundCloud bear that out) — some music will always be functional for me. But I also make a concerted effort to discover new music, or at least Thanks to all my friends who are patient with me when I discover an artist that has been popular for years in different scenes that I am just oblivious to… .

For years now I’ve been listening to less music on Spotify and instead choosing other platforms (SoundCloud, YouTube) and mostly purchasing music on Bandcamp (and occasionally Beatport and the iTunes store when needs must). I wrote about my tactics this time last year: My evolving music discovery pipeline.

As a teen ripping CDs from the library, trolling music blogs for free MP3s and mixtapes, discovering Livejournal groups trading full artist discographies, writing down song lyrics that I heard on the local college radio station or in the store I worked at, I felt a deep curiosity and joy associated with music discovery. And I don’t want to lose that as time goes by!

Like Hanif Abdurraqib points out in A Year of Listening Beyond the Algorithm:

I have kept up my eager pursuit of new music all these years later, because I refuse to believe that the hope of brain-shifting listening experiences must be abandoned with childhood.

I feel the same way — I want to seek out those experiences, to feel something when I listen to music, I want to be challenged and hear new sounds and new tempos and new dynamics.

And it’s working — my music taste has changed since I was 15. There are consistent themes in what I listen to (mad harmonies and a moment where the instruments drop out will always get me) and how I listen to music.

Discovery takes work — it’s not comfortable to always listen to something new. As such, I do my discovery in waves. I’m not always working, but I take steps to seek out new music, genres, producers, record labels, and follow my curiosity.

Discovery for me doesn’t often happen algorithmically. I do covet an excellent autoplay recommendation experience (when SoundCloud’s recommendations hit, they hit hard), but listening to personalized playlists quickly started to feel like a chore with little payoff; a weekly task to be checked off:

√ It’s Monday, so it’s time to listen to Discover Weekly before it goes away.

√ It’s Friday, listen to Release Radar to find out what was released today.

Most of the music in Discover Weekly didn’t stick with me, and Release Radar was reduced to single tracks instead of full albums, often trickling out an entire album’s worth of tracks over weeks of playlists. The more I listened, the more I got in the habit of clicking through on each new track to see if there was secretly a full album of music that I was missing out on.

Nowadays, I’ve abandoned those algorithm-driven playlists.

Instead, I focus more on the personal connections — channels across various social chats where people share music that we love (or that made us feel something) with each other — as well as exploring the track lists of DJ sets on YouTube and SoundCloud, favoriting new releases and collaborations with other producers, and reading posts from music bloggers or others, sharing music that simply could not stay unheralded.

Some ways I was steered toward or discovered new music in 2025 was through podcasts, music blogs, or more organic discoveries and recommendations.

The role of podcasts #

Podcasts had an unexpectedly strong role in my music listening in 2025. Unexpected largely because I don’t listen to podcasts very often, but I did discover a new podcast in 2025 — Life of the Record — so the novelty probably helped.

In 2022, I also had a noticeable spike in listening behavior due to a podcast — I listened to a lot of Frightened Rabbit immediately after listening to a podcast about the band and the death of the frontman.

As I mentioned in my favorite songs section, I listened to a lot of Sam Cooke in 2025 because of the Hit Parade episodes about Sam Cooke, Don’t Know Much About History. I’d heard some songs by him, but I didn’t realize just how deep his catalog was of good songs — (What A) Wonderful World is not the Louis Armstrong song, but instead a cute ditty about how much being loved can change your outlook on life. At least that’s my read on it!

Another great set of Hit Parade episodes (that didn’t influence my listening much) was Only Girl in the World Edition, about Rihanna. Powerhouse superstar showed up, made hella albums, and is now a retail mogul. Excellent arc, no notes.

Discovering the podcast Life of the Record also affected my listening, partially because the first episode I listened to was about the Stars album Set Yourself on Fire, which was maybe the first Stars album I heard? Revisiting that, combined with the memory of how unexpectedly raucous they were live for such a delicate sounding (at times) band, turned me back onto their music for a time.

Meanwhile, the podcast also covered a favorite Manchester Orchestra album of mine, Mean Everything to Nothing, which I’d already listened to a few times in 2025 while in a moody reminiscence a la Frightened Rabbit. Inspired by the podcast, I gave it a few more listens, and listened to the albums before and after it for good measure.

End-of-year music wrap-ups #

Other people posting their favorite music also influenced my music into the next year. Every year, Sean from Said the Gramophone puts out a top 100 songs list of the year. I love this for multiple reasons:

- Music blogs have had a huge impact on my music taste and I love anything that keeps music blogging alive.

- Songs are easier to listen to than full albums when processing for discovery.

- The list spans genres and reminds me of how much I like songwriters and indie rock and helps me key in to new genres I might like.

Why do I mention this? The only reason I listened to Mk.gee and Waxahatchee at all in 2025 because of that list. And I ended up liking both of their albums quite a bit and listening a lot.

Mk.gee’s album Two Star & the Dream Police ended up my most-listened-to album of the year — and all of my listening happened in January. Sorry Mk.gee, I guess in the summer I forget that I like indie rock.

I haven’t listened to much Waxahatchee since seeing them live (opening for Rilo Kiley) in October 2025, but I spent a lot of early 2025 winter listening to their album Tigers Blood in full, and they ended up my fourth-most-listened-to artist of the year.

Joshua Idehen was a new discovery in 2025, also thanks to the 2024 list.

I treasure the Said the Gramophone post from Sean because my conduits for indie rock discovery are thin on the ground now that I don’t listen to college radio (or DJ in it during the tail end of the heyday). Mostly I’m relying on recommendations from friends.

DJ sets have a unique way in electronic music of introducing you to similar artists and producers, but for indie rock artists, you have to dig deeper to find the occasional collaborators, or go see the artists live and make sure to catch the openers, or similar. It’s a lower-traffic and more active discovery mechanism to follow those discovery threads through without resorting to algorithms.

Organic discoveries #

As I mentioned earlier, I discovered 700 “new” artists in 2025, of which several were new favorites. But how did I discover them? Most of them, I discovered organically…

- The Beaches I discovered ( I technically discovered them first in 2017, listening to them 7 times that year, but I listened to them 30 times in 2025 so it feels like a proper rediscovery. ) after a friend at work recommended them, then they released an excellent Tiny Desk Concert.

- GLOCKTA released an EP on a record label, ec2a, that I’d previously purchased music from. I took a chance on an EP from them, listening in the background, and boy did it pay off.

- IN PARALLEL I discovered purely because they booked a show in San Francisco. I keep track of shows happening in the city (so I can go to them, of course) and based on the promoter and the venue I realized that I’d probably like them, so I looked up a set and it was great.

- Dr Dubplate I discovered thanks to the Boiler Room DJ set where he played b2b with Y U QT, favorite producers of mine.

- Faster Horses I also discovered thanks to the ~ network of producers ~ that I follow on Bandcamp and elsewise, hearing his tracks played out in some DJ sets I enjoyed and eventually tracking him down on Bandcamp.

These sorts of organic discoveries really stuck with me, because making the discovery took some effort (and a little risk), and it was rewarding.

Why I talk about music discovery with Spotify Wrapped #

Maybe I talk about this effortful music discovery every year, but it’s so important to me. Music is a part of culture, and culture is something that we share as a community — it’s something that we make and participate in, not something that happens to us. It’s important to me that I engage with it directly, instead of passively.

Liz Pelly’s outstanding book Mood Machine makes it clear that Spotify has chosen to focus on a specific target consumer market — the “lean-back” listener. As Pelly points out on page 32 of Mood Machine:

In the streaming era, the industry identified a new type of target consumer: the lean-back listener, who was less concerned with seeking out artists and albums, and was happy to simply double-click on a playlist for focusing, working out, or winding down.

Spotify chose to focus primarily on those target consumers, and as part of that move, set up internal structures that built playlists using vast troves of collected and computed metadata.

Instead of building an application that rewarded active listening and focused on adventurous, educational, or thoughtful curation (what might build more of a music culture or community), Spotify chose to “follow the data” of what users of the service were already listening to, and emphasize this “lean-back” listening behavior:

there was nothing inherently neutral about setting up a system that wrapped up all of a song’s worth in its replay value. To do so is to suggest that a song’s potential to ignite mass enthusiasm, and thus mass streams—or its capacity as background fodder, streaming endlessly, unnoticed—should determine its worth.

What Spotify chooses, quite literally, to reward, is the more passive user behaviors like “frequently replayed” or “infrequently skipped”. Spotify has built their business around optimizing for metrics like this, and as such, has shifted (or at least focused) the attention of the music industry accordingly. On page 44 of Mood Machine, Pelly continues:

By championing the lean-back listener, Spotify helped popularize a resurgence of interest in “functional music,” the industry’s current preferred way to describe music for sleeping, studying, chilling, focusing, etcetera. Today, functional music is a defining phenomenon of the streaming era, especially mood music for wellness and productivity, which self-improvement culture increasingly renders the same.

It’s ordinary and typical to listen to music in the background of tasks. I also listen to music this way—I focus better when I’m listening to music, and often listen to music while performing other tasks. I have music on in the background while writing these very words (a track by tennyson). Even for me, “listening to music” is rarely a primary task.

Listening to music in the background, however, doesn’t inherently require “lean-back” listening behavior. I still remember the grooves and the patterns of the Explosions in the Sky album The Earth Is Not A Cold Dead Place, ingrained in my memory after countless repeat background listens in college.

These days, I intentionally try to reward “sit up” listening for myself, and pay attention to the music that sparks something in me (especially when I’m engaged in more mindless activities like commuting to work).

While I still engage in mindless background music listening, I try to intentionally curate the background by listening to DJ sets or live music sets Like HAAi b2b Romy at the Lot Radio 01-16-2026! and which might introduce me to some new-to-me music. Perhaps this week I’ll listen to some newer Explosions in the Sky or other post-rock albums.

The rating practice that helps lead to music acquisition (if on a streaming site) or frequency of listens (if I already own the song) is my way of recognizing and rewarding the “sit up” listening.

If I’m listening to new music that I just bought or an autoplay recommendation deep in SoundCloud, I take action if a track makes me sit up and take notice. I’ll take a moment to at least heart the track, add a rating, and possibly go further to explore a discography, listen to a few other tracks, or boost the track to others.

I don’t mention this to espouse my personal music listening habits as a virtuous paragon, but rather to showcase an alternate method of engagement with music and streaming services, that goes beyond the default of a Daily Mix in a streaming service and how I have found a way to carve out my own meaning with the media and services I engage in day-to-day.

What’s to come in 2026? #

More of the same discovery practices, I expect, with a bit more effort toward indie rock and pop music. The Popjustice folks have some great recommendations, but I rarely encounter them in my usual channels. Indie rock, as I’ve mentioned throughout this post, is not as easy to organically discover (when compared to tracks in an electronic music DJ set).

I think some college radio listening might be in my future to help with discovering more non-electronic music, as well as soliciting playlist collaborations with friends. I don’t want to be so late to the next MUNA, Chappell Roan, or Caroline Polachek — an earlier discovery means more time to enjoy!

Having finished reading Mood Machine in 2025, I have a lot of books on similar or adjacent themes that I’m hoping to get to this year. I’ve built them into a syllabus of sorts, and I’d love recommendations.

Look forward to more from me on related topics this year…

-

This year, a calculation error that I made in my math really revealed itself — I thought I had listened to 276,606 minutes of music. Which sounds plausible until you remember the most well-known song from RENT, and that there are 525,600 minutes in a year. I listen to a lot of music, but 12+ hours of music per day is wildly inaccurate. The calculation I perform does several things: First, retrieve my listening data, then look up each track that I listened to that year and append the track_length from my iTunes library, if it exists, to the event. Separately, I calculate an estimated track_length based on the average track_length of all songs I listened to in the year. For each track_name, coalesce the actual track_length and the estimated track_length to make sure each track has a length listed. Then count the track_names and pass through the track length, multiply the count by track_name for each track_length and sum it, then transform length into minutes. I had an error where I split my count by both track_name and track_length, which somehow caused a track I listened to 5 times to show up as 275 listens. Lessons to always gut check my data analysis results, and thank you to Scott online for identifying the mistake! ↩︎

-

TIL that St. Cecilia is the patron saint of music. ↩︎