What is Old is New Again: Following Up

Books are holding their own against e-books, vinyl is making a comeback, film if it isn’t making a comeback, is holding steady since the Kodak bankruptcy. This cycle gives voice to what we want from our technology, devices, and everyday contraptions. In my first post on this matter I reasoned that it comes down to the experience, and that “The contrast between a digital and an analog experience can alter interpretations of media."

This still holds true, and the nostalgia and authenticity attached to an analog experience has led digital technology to be reworked, in a way, to take advantage of these emotions.

Books #

Books and e-books can work in tandem, but the medium might matter more when it comes to comprehension: "“We bombarded poor psychology students with economics that they didn’t know,” she says. Two differences emerged. First, more repetition was required with computer reading to impart the same information. Second, the book readers seemed to digest the material more fully.” It seems fairly true that “it may be harder to grasp material consumed in e-book form, where the words slide by as if on ice skates, than in print.” The tangibility of paper books, then, has real and established value for memory and learning.

The role of design in books has been hurt by e-books and the role of technology, but perhaps that has more to do with platform design: “The more we are able to push and pull content in and out of the cloud, the more it seems that the content itself lacks an inherent visual identity. In tangible terms, that means that a book, though painstakingly designed inside and out, may carry none of its visual properties with it when it’s rendered on a Kindle.” A book is painstakingly designed as a book, but perhaps if it were painstakingly designed as an e-book, the opposite challenge would emerge. Can an e-book be designed in such a way that its design can be translated in print as well?

The same article continues, “The more that digital becomes the native format of content, the more its influence will be apparent on analog content”. According to this essay, paper books will work harder to emulate digital e-books as those become the norm. I think it’s much more likely, however, for paper books to embrace their format and the value and design that paper allows, such as a book cover for Fahrenheit 451 where the spine is made of matchbook striking paper. This sort of design cannot be replicated in digital form, as it requires a certain tangibility to be meaningful. Digital books as well, would need to embrace their format as a virtual storytelling medium that allows techniques such as hyperlinks, and some form of engagement. E-books can be used to end a passive engagement with a story, as:

That can certainly be done with an e-book: a choose-your-own adventure book would no longer be limited by the number of pages.

An additional influence of e-book design on book design could be to transform the role that books play in our lives as objects. Indeed as this Slate essay points out, “the book has always been as much a design object as a vehicle to enable the experience of reading. (In fact, publishers are fighting the physical book’s demise with a renewed effort to use innovative methods to make books into beautiful objects that we want to touch and hold.)” Paper books can take advantage of their tangibility status and become closer to works-of-art to be displayed, while e-books lend themselves to the more private business of pure consumption.

The function and format of books have always influenced and driven their design. A book from 1759 is nearly the same size as a book displayed on a smartphone screen. As Clive Thompson recounts, “That small-page format was quite common back in the 18th century. It’s known as octavo duodecimo — with pages that are about 6 inches by 9 inches. The entire Conjectures is only about 8,000 words long, but it was common to print essays in this pretty little style, because it had great ergonomics: It made for easy one-handed reading and portability.” As he examines why that format grew out of style, he points out that with the rise of hardcovers, there was the need to produce weighty books. However:

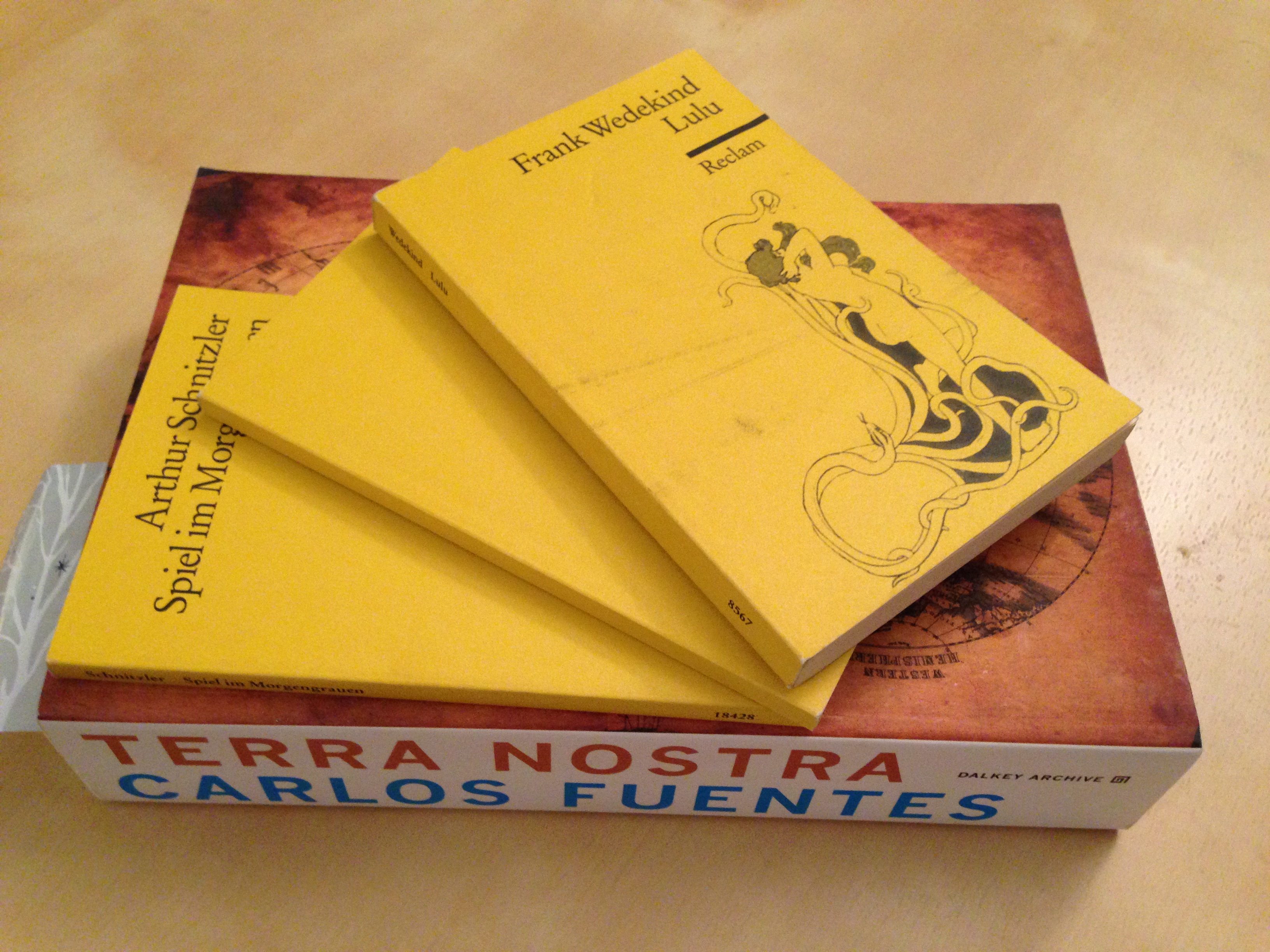

Thus, “the ergonomics of smartphones as reading devices are not only kind of rad, but historically so.” This historical fluctuation of format based on consumption and function means that for the same to happen lately isn’t too far of a stretch. Indeed, small, pocket sized books exist very cheaply in Germany (can’t vouch for elsewhere), but less often in America.

Some objects have inherent value when rendered in analog format, and should continue to flourish regardless of the influence of the digital. A new project called Wink Books by some of the folks behind Cool Tools works to celebrate books that “deserve to be printed on paper”. As the people behind Wink Books put it:

“Wink scours bookstores, libraries, flea markets, and online retailers looking for books that you must experience; books that are sensual, three dimensional, robust. We seek out artifacts that you must hold in your hands or unfold in your lap. Wink collects books that optimize what books do best on paper: open up new worlds. Our test for Winkdom is simple: would this book work as an ebook? If yes, we ignore it. Rather we gather for you the best books that work on paper. Wink books will never go obsolete – they can still be enjoyed in a hundred years. As much as possible, we go out of our way to find paper books that are little known treasures, that are uncommon and unconventional, and yet are still available (that is, we don’t feature “rare” books)."

The allure of (analog) books over electronic, digital books is in the experience: how these books appeal to the senses in ways that digital books are incapable of reproducing.

Many new media formats are experimenting with the old format of serialization and short-format to bring some of the interaction and the “newness” back to books and storytelling. Twitter is a popular medium for storytelling, surprisingly, “because of the intimacy of reaching people through their phones, and because of the odd poetry that can happen in a hundred and forty characters." Teju Cole has been embracing the limitations and techniques in this format, most recently with his story “A Piece of the Wall” crafted in a custom timeline.

Beyond Twitter, apps such as Rooster employ serialization as well: “The app’s approach is to deliver novels in bite-sized chunks. Each segment should take about 15 minutes to read, and they arrive when you choose, whether it’s every morning before work; every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday; or whatever. There are two books offered every month — a contemporary title and a classic novel that’s supposed to offer “a conversational counterpoint.””

Rooster isn’t the only app out there, as ““Amazon announced a new Serials program” last fall, in which novels are published an episode at a time, rather than all at once. A startup called Plympton ran a successful Kickstarter to support its own serialized fiction efforts (it’s also partnering with Amazon). And serialization is part of the model at another digital publishing startup called Coliloquy.” This trend operates counter to the “broader conversation around how media consumption is changing, with no one willing to wait for anything anymore. At least, that’s what I keep hearing and reading: Everything will be released everywhere immediately because waiting is so 20th century, man.” Serialized fiction and these digital techniques recapture the Victorian patterns of Serial Literature and use it to remake the stereotypes surrounding digital media and storytelling that have been thrust upon them by Netflix-esque binge-watching.

As serialized books were once popular and return today, so too does the semi-private newsletter. “The last year or so has seen an intriguing renewal of a genre from the early years of the internet: the email newsletter. A couple of months ago Alexis Madrigal described this development as a natural and healthy response to a never-ending and increasingly vast stream of online data”. While the past involved similar content, as “In 1753 Grimm began to write and edit La Correspondance littéraire, philosophique et critique, a newsletter about cultural events that was meant to supplement and when necessary correct official news sources, which were subject to rigorous censorship.” the purpose of writing newsletters has changed dramatically in some locales. Once used to subvert censorship and provide an alternate source of news, newsletters now serve as careful curative digests of the news, seeking to find the importance (or the intriguing, in the case of Madrigal), of the firehose of the web.

Although books may help you retain content better than e-books, some countries are digitizing all of their books, but in the United States, the paper lobby is discouraging the ever-increasing move to digital. This may seem backward or counter to progress (indeed, the federal government is one of the larger users of some of these old technologies), but in fact too little attention is being paid to the environmental costs of producing electronic devices and disposing of them, such as batteries and rare earth minerals, not to mention the lack of universal and affordable access to the Internet(link covers only United States). The environmental impact of paper, at least, is far more consumer-transparent.

Nostalgia surrounding technologies replaced or subsumed by the Internet and the web is encapsulated in the recent Paper advertisement for Facebook’s app:

Yet as Chris Butler continues, he takes to task what is hidden in advertisements and nostalgic-navel-gazing practices such as this: They “don’t show you the massive, energy sucking data centers behind the tech in their future worlds — the 40,000 megawatt blocks of nothing but snarls of cable and plastic. But they’re there somewhere. They have to be, unless they figured out some other way to store all our selfies and status messages, and some other way to keep the lights on besides burning things.” These environmental impacts of our digital tech will become, and must become a larger part of the conversation surrounding digital technology.

Art #

Paper (the medium) “is a star of this Biennial, with dozens of books and printed material. “Now that we have access to more archival material, we are all preoccupied with how we can reanimate it and create living histories,” Mr. Comer said.” The Whitney Biennial, which attempts to portray a slice of contemporary art movements, is in part celebrating the function of paper. “The first Arts and Crafts movement, in England, challenged the taste of the Victorian era. Now the handmade aesthetic is flourishing again, Ms. Grabner said. “As so much moves to the digital world, there is a movement of slowing art and life down.”” The trend has been to recapture the old, to slow down our connections and our consumptions, and understand it anew through art and handmade pieces.

Another paper element of the Biennial is the leporellos, which

Why has paper (and words) been so celebrated as an art form in this Biennial?

This role of paper, handmade art, and words as “older” technologies lends themselves as valuable works to be enshrined in museum exhibits.

As some museums treasure the role of paper, handmade art, and words in contemporary art, another (online) museum is making painstaking effort to preserve “vanishing and endangered sounds” such as “The sound of a dial telephone, a walkman, a analog typewriter, a pay phone, a 56k modem, a nuclear power plant or even a cell phone keypad are partially already gone or are about to disappear from our daily life." The online museum also makes the effort to accompany the sounds with interviews, so as to “give an insight in to the world of disappearing sounds.” This museum functions as a repository for the old, the vanished, and the nostalgia for outdated technologies.

Music #

Beyond miscellaneous everyday sounds, music has become a medium in which artists and listeners alike make the effort to recapture what has been lost in the digital era. Vinyl is experiencing a resurgence, as I’ve discussed before, to such a degree that Pioneer teased a new turntable model at Musikmesse 2014. There is even a vinyl-by-mail subscription service if you’re inclined to partake.

Vinyl has certain medium-specific quirks that artists can take advantage of. While in digital music-making, vocal pitches can be tweaked by software, and some DJs use laptops instead of record players, vinyl as a medium allows techniques like scratching that can be falsely replicated by digital sounds. It also lends itself well to other playful functions, like an element observed in this passage by a woman who listens to all of her husbands vinyl records and blogs her impressions:

“The last song, “It’s Obvious” repeats the phrase “you’re equal but different” over and over again at the end. WOAH then it sounds like it’s over but it starts again, but then just keeps playing over and over again like it’s skipping! But it sounds intentional! I just said to Alex, “is this skipping or is it supposed to sound like this?” He asked me if the needle is on the last groove of the record, which it is. Then he said, “There’s a thing called a lock groove, sometimes people put a repeating phrase on the last groove and let it play over and over again.” Me: “That’s awesome!!” He also told me that some times artists will etch secret message on the “inside ring” of the record, but we looked and this one just says “Birmingham” and Belfast, Bristol, Brixton.” If that is a secret message, I don’t know what it means. Still pretty cool though. I’m really into lock grooves you guys, you can’t do that on an mp3 now can you?”

It’s clear the vinyl offers something in the experience, and not just for DJs. As I recounted in my last post, much of it revolves around a search for authenticity, which is just the same craving that Neil Young is banking on for the success of his new Pono music player.

Pono is the culmination of the “quest” he’s been on “for a few years now, to revive the magic that has been squeezed out of digital music." By blending the true sounds found only in vinyl with the convenience of digital music, Pono brands itself as “a grassroots movement to keep the heart of music beating.” which “aims to preserve the feeling, spirit, and emotion that the artists put in their original studio recordings." Ultimately, with this music player, you can “hear the nuances, the soft touches, and the ends on the echo – the texture and the emotion of the music the artist worked so hard to create."

In the FAQs, the Kickstarter campaign funding this music player directly addresses perhaps their largest market, the audiophile. In fact, the player takes special pains to remove all traces of digital sound from their digital music player.

[“The digital filter used in the PonoPlayer has minimal phase, and no unnatural (digital sounding) pre-ringing. All sounds made (including music) always have reflections and/or echoes after the initial sound. There is no sound in nature that has any echo or reflection before the sound, which is what conventional linear-phase digital filters do. This is one reason that digital sound has a reputation for sounding “unnatural” and harsh."…“The DAC (Digital-to-Analog Converter) chip being used is widely recognized in the audio and engineering community as one of the best sounding DAC chips available today."](https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1003614822/ponomusic-where-your-soul-rediscovers-music#project_faq_83689 " href=“http://www.fastcolabs.com/3027720/neil-youngs-crowdfunded-quest-to-fix-your-disastrous-mp3-situation">"At launch, the PonoMusic store will focus on selling albums rather than individual tracks like iTunes. Prices will v”)

The format of the music being sold in the PonoMusic store is clearly marketed toward the vinyl-aficionados as well, by the fact that “At launch, the PonoMusic store will focus on selling albums rather than individual tracks like iTunes. Prices will vary depending on record label preferences, but on average they are expected to range from $15 to $24 per album”. Vinyl sold singles back when it was the only medium for audio around, but now it trafficks largely in LPs and the occasional independently released 7-inch EP.

The Kickstarter page goes through great lengths to detail the differences between the different bit rates of digital music files available and which ones the Pono player specifically caters to, namely the FLAC (Free Lossless Audio Codec), which preserves from 1411 to 9216 kbps compared to the 192 to 256 kbps of an mp3 file. As an article about the player makes clear,

The conclusion the author of that article comes to is in favor of the player, recognizing that “Pono does sound different. It surfaces new things to the listener. As many have pointed out, the sound is “warm,” not unlike the analog sound of high-quality vinyl. The results will undoubtedly vary from album to album and speaker to speaker, but on the whole it does sound fuller and more pure than the audio files we’re used to” The purity of analog music is something that Young and the Pono team likens to photography, another medium subsumed by the digital revolution but which has begun to see a renaissance of sorts when it comes to film. As the Kickstarter FAQs detail,

This presence evoked by a truly great quality sound file or photograph is something that Pono attempts to recreate.

Photography #

As Nathan Jurgenson dissects in an essay about the use of faux-vintage filters in digital photography

“For many, and especially those using faux-vintage apps, photography is primarily experienced in the digital form: snapped on a digital camera and stored and shared via digital albums on computers and websites like Facebook. But just as the rise and proliferation of the mp3 is coupled with the resurgence of vinyl, there is a similar reclaiming of the aesthetic of the physical photo. Physicality, with its weight, smell and tactile interaction, grants a significance that bits have not (yet) achieved. The quickest way to invoke nostalgia for a time past with a photograph is to invoke the properties of the physical, which is done by mimicking the ravages of time through fading, simulated film grain and scratches as well as the addition of what appears to be photo-paper or Polaroid borders around the image.”

There is a very valuable element of authenticity derived from simulating film, which can easily be extended to the use of film itself.

One particular film, Tri-X by Kodak (used by “Henri Cartier-Bresson, Garry Winogrand, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Josef Koudelka and most of the finest of the photographers who worked for the Magnum agency” is valued for those authentic, yet forgiving qualities.

Using film for photography rather than relying on digital “goes to the heart of how we see and what we see and what we may be losing as billions of casual, digital snaps are taken daily and as photographic integrity is subverted by the dead, flawless, retouched faces of actors and models that gaze blankly out at us."

A photographer revels in the imperfections of film, much like audiophiles treasure the subtle scratches and clicks of a vinyl record, rhapsodizing that ““Grain is life,” Corbijn says, “there’s all this striving for perfection with digital stuff. Striving is fine, but getting there is not great. I want a sense of the human and that is what breathes life into a picture. For me, imperfection is perfection.” Just as DJs continue to debate the merits of using vinyl or laptops to conduct their sets (though for high profile DJs like Daft Punk, there is no debate), photographers disagree about film and digital: “Film versus digital, McCullin points out, is still a debate among professionals and they are not talking about megapixels. Film is about more than just resolution, it is about authenticity. Film has other, more mysterious qualities.”

This trend has continued beyond just professional photographers, into the consumer market as well.

Film also sits in counterpoint to the immediacy of the digital that was decried by book readers (leading to the comeback of serialization techniques), as a photographer recounts:

Film is authentic, slow, and grainy. Digital is inauthentic, immediate, and overly clean. Vinyl is authentic, grainy as well, and a medium with its own quirks. Digital music is lossy, unnatural, and reduced in most formats to a recognition of a song rather than a true representation of it. And books are an experience, spatially valuable for memory, and a medium with its own quirks, such as pop-up books, that can only exist in paper books. E-books cause words to slide off the page, neglect visual content, and scroll infinitely.

However, digital photography is booming, and the faux-vintage filters examined by Jurgenson are just as popular as the photography itself. Vinyl is making a comeback, and digital music is being remade to recapture the sounds lost in compression. Books and e-books continue to coexist, and storytelling has taken on new (old) formats of serialization that live in exclusively digital media like Twitter and apps. The cycle continues as we attempt to use digital media to recapture and reclaim the “authenticity” lost to the past. A fetishization of perhaps “inferior” media, yet imperfection is human, authenticity is found in the graininess and the grooves, and digital for now, remains a bit too far in the uncanny valley to seem authentic and real.