Streaming, the cloud, and music interactions: are libraries a thing of the past?

Several years ago I wrote about fragmented music libraries and music discovery. In light of the overwhelming popularity of Spotify and the dominance of streaming music (Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, Tidal, and others), I’m curious if music libraries even exist anymore. Or, if they exist today, will they continue to exist?

My guess is that the only people still maintaining music libraries are DJs, fervent music fans (like myself), or people that aren’t using streaming music at all (due to age, lack of interest, or lack of availability due to markets or internet speeds).

I was chatting with a friend of mine that has a collection of vinyl records, but she only ever listens to vinyl if she’s relaxing on the weekend. Oftentimes she’s just asking Alexa to play some music, without much attention to where that music is coming from. With Amazon Music bundled into Amazon Prime for many members, people can be totally unaware that they’re using a streaming service at all. I’d hazard that this interaction pattern is true for most people, especially those that never enjoyed maintaining a music library but instead collected CDs and records because that was the only way to be able to listen to music at all.

Even my own habits are changing, perhaps equally due to time constraints as due to current music technology services. I used to carefully curate playlists for sharing with others, listening in the car, mix CDs, and for radio shows. These days I make playlists for many of those same purposes on Spotify, but the songs in my “actual” music library (iTunes) aren’t categorized into playlists at all anymore, and I give the playlists I make on my iPhone random names like “Aaa yay” to make the playlists easier to find, rather than to describe the contents.

I’m limited by storage size in terms of what I can add to my iPhone, just like I was with my iPod, but that shapes my experience of the music. Since I’m limited to a smaller catalogue, I’m able to sit with the music more and create more distinct memories. There are still songs that remind me of being in Berlin in 2011, limited to the songs that I added to my iPod before I left the United States because the internet I had access to in Germany was too slow to download new music and add it to my iPod.

Nowadays, I am less motivated to carefully manage my iTunes library because it’s only on one device, whereas I can access my Spotify library across multiple devices. That’s the one I find myself carefully creating folders of playlists for, organizing and sorting tracks and playlists. A primary reason for the success of Spotify for my listening habits is the social and collaborative nature of it. It’s easy to share tracks with others, make a playlist for a DJ set that I went to to share with others, contribute to a weekly collaborative playlist with a community of fellow music-lovers, or to follow playlists created by artists and DJs I love. My local library can give me a lot, but it can’t give me that community interaction.

Indeed, in 2015 that’s something I identified as lacking. I felt that it was harder to feel part of a music culture, writing:

“It’s harder than it used to be to feel connected with music. It’s not a stream or a subculture one is tapped into anymore, because it’s so distributed on the web. There’s so much music, and it lives in so many different services, that the music culture has imploded a bit.”

I feel completely differently these days, thanks to a vibrant live music community in San Francisco. I loathe Facebook, but the groups that I’m a part of on that site enable me to feel connected to a greater music scene and community that supplement my connection to music and music discovery. Ironically, Facebook groups have also helped my music culture experience become more local. The music blogs that I used to be able to tap into are now largely defunct, or have multiple functions (the burning ear also running vinyl me please, or All Things Go also providing news and an annual festival in DC). Instead yet another way I discover new music is by paying attention to the artists and DJs that people in these Facebook groups are talking about and posting tracks and albums from.

Despite the challenges of a local music library, I keep buying digital music partially because I made a promise to myself when I was younger that I’d do so when I could afford to, partially to support musicians and producers, and partially because I distrust that streaming services will stick around with all the music I might want to listen to. I’d rather “own” it, at least as best as I can when it’s a digital file that risks deletion and decomposition over time.

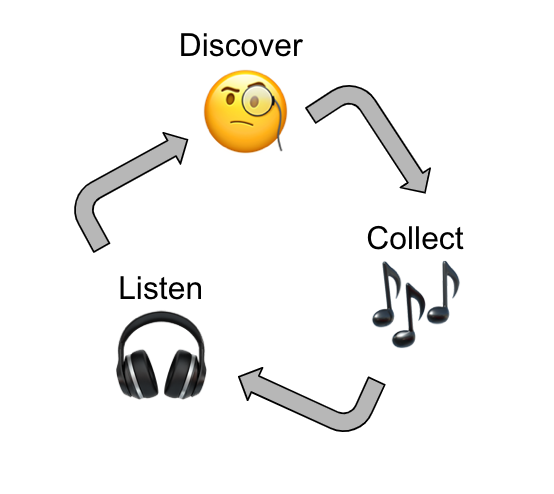

Music discovery in the past was equal parts discovery and collection, with a hefty dose of listening after I collected new music.

I’d do the following when discovering new music:

- Write down song lyrics while listening to the radio or while working my retail job, then later looking up the tracks to check out albums from the library to rip to my family computer.

- Follow music blogs like The Burning Ear, All Things Go, Earmilk, Stereogum, Line of Best Fit, then downloading what I liked best from their site from MediaFire or MegaUpload to save to my own library.

- Trawl through illicit LiveJournal communities or invite-only torrent sites to download discographies for artists I already liked, or might like.

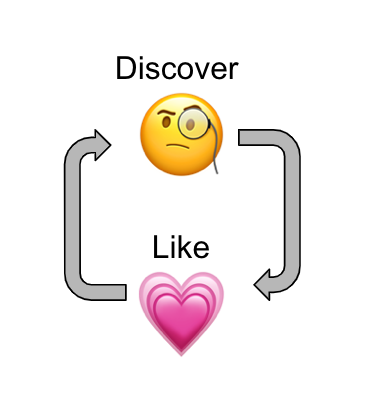

Over time, those music blogs shifted to using SoundCloud, the online communities and torrent sites shuttered, and I started listening to more music on streaming sites instead. The loop stopped going from discovery to collection and instead to discovery, like, and discovery again.

Find a new track, listen, click the heart or the plus sign, and move on. Rarely do you remember to go back and listen to your fully-compiled list of saved tracks (or even if you do, trying to listen to the whole thing on shuffle will be limited by the web app, thanks SoundCloud).

This type of cycle is faster than the old cycle, and more focused on engagement with the service (rather than the music) and less on collecting and more on consuming. In some ways, downloading music was like this too. When I accidentally deleted my entire music library in 2012, the tatters of my library that I was able to recover from my iPod was a scant representation of my full collection, but included in that library was discographies that I would likely never listen to. Now that it’s been years, there have been a few occasions where I go back and discover that an artist I listen to now is in that graveyard of deleted songs, but even knowing that, I’m not sure I would’ve gotten to it any sooner. I was always collecting more than I was listening to.

Streaming music lets me collect in the same way, but without the personal risk. It just makes me dependent on a third-party entity that permits me to access the tracks that they store for me. I end up with lists of liked tracks across multiple different services, none of which I fully control. These days my music discovery is now largely driven by 3 services: Spotify, Shazam, and Soundcloud. Spotify pushes algorithmic recommendations to me, Shazam enables me to discover what track the DJ is currently playing when I’m out at a DJ set, and Soundcloud lets me listen to recorded DJ sets as well as having excellent autoplay recommendations. In all of them I have lists of tracks that I may never revisit after saving them. Some of them I’ll never be able to revisit, because they’ve been deleted or the service has lost the rights to the track.

In 2015 I lamented the fragmentation of music discovery, but looking back, my music discovery was always shared across services, devices, and methods—the central iTunes library was what tied the radio songs, the library CDs, the discography downloads, and the music blog tracks together. The real issue is that the primary music discovery modes of today are service-dependent, and each of those services provides their own constructs of a music library. I mentioned in 2015 that:

“my library is all over the place. iTunes is still the main home of my music—I can afford to buy new music when I want —but I frequent Spotify and SoundCloud to check out new music. I sync my iTunes library to Google Play Music too, so I can listen to it at work.”

While this is still largely true, I largely consume Spotify when I’m at work, listen to SoundCloud sets or tracks from iTunes when I’m on-the-go with my phone, and listen to Spotify or iTunes when I’m on my personal laptop. That’s essentially 2.5 places that I keep a music library, and while I maintain a purchase pipeline of tracks from Spotify and SoundCloud into my iTunes library, it’s a fraction of my discoveries that make it into my collection for the long term. The days of a true central collection of my library are long since past.

It seems a feat, with all these digital cloud music services streaming music into our ears, to have a local music library. Indeed, what’s the point of holding onto your local files when it becomes so difficult to access it? iTunes is becoming the Apple Music app, with the Apple Music streaming service front and center. Spotify is, well, Spotify. And SoundCloud continues to flounder yet provides an essential service of underground music and DJ sets. Google Play Music exists, but only has a web-based player (no client) to make it easier to access and listen to your local library after you’ve mirrored it to the cloud. Streaming is convenient. But streaming music lets others own your content for you, granting you subscription access to it at best, ruining the quality of your music listening experience at worst. A recent essay by Dave Holmes in Esquire talks about “The Deleted Years”, or the years that we stored music on iPods, but since Spotify and other streaming services, have largely moved on from. As he puts it,

“From 2003 to 2012, music was disposable and nothing survived.”

Perhaps it’s more true that from 2012 onward, music is omnipresent and yet more disposable. It can disappear into the void of a streaming service, and we’ll never even know we saved it. At least an abandoned iPod gives us a tangible record of our past habits. As Vicki Boykis wrote about SoundCloud in 2017,

“I’m worried that, for internet music culture, what’s coming is the loss of a place that offered innumerable avenues for creativity, for enjoyment, for discovery of music that couldn’t and wouldn’t be created anywhere else. And, like everyone who has ever invested enough emotion in an online space long enough to make it their own, I’m wondering what’s next.”

I’ll be here, discovering, collecting, liking, and listening for what’s next.