My evolving music discovery pipeline

Over the years the dominant genres in my music taste have evolved, from mostly pop-punk in the early aughts, to primarily indie rock and bloghouse music in the late aughts, to house in the early tens, and now a much wider variety of electronic music, including UK garage and some trance.

As what and how I listen to music has changed over the last 20 years, the way I discover music has too.

Digital streaming platforms like Spotify are so pervasive now that it’s almost hard to remember the days when I was discovering music primarily by listening to the radio and reading music blogs, along with the occasional visit to the CD section of my local library.

5 years ago, algorithmic discovery via streaming services was a primary part of my music discovery process. In 2019, I wrote:

These days my music discovery is now largely driven by 3 services: Spotify, Shazam, and Soundcloud. Spotify pushes algorithmic recommendations to me, Shazam enables me to discover what track the DJ is currently playing when I’m out at a DJ set, and Soundcloud lets me listen to recorded DJ sets as well as having excellent autoplay recommendations. In all of them I have lists of tracks that I may never revisit after saving them. Some of them I’ll never be able to revisit, because they’ve been deleted or the service has lost the rights to the track.

Nowadays, my music discovery approach is somewhat more community-oriented, but still supplemented by many of the same tools I was using 5 years ago. One risk of those tools and the algorithmic discovery on streaming services is falling into an endless loop of discovering tracks, liking them, and moving on to discover more tracks.

I enjoy discovering music. For me, discovering music isn’t so much a process as a practice, something that I actively continue to do because it brings me great joy and also because I read at some point that most people form their music taste in their teens and never expand it, and I was determined to be different. But I also discover new music because I like music so much — which means I also need to take time to listen to what I’ve discovered, instead of getting caught up in digging up new new new new.

To try to balance out the allure of the new, I’ve tried to build a Bandcamp-to-offline-listening pipeline. Shortening the discovery to acquisition pipeline means that I can spend more time in the “burn in” period with a shorter list of songs (with the added bonus of being able to pay more money to more artists that I care about supporting).

Music discovery on Bandcamp #

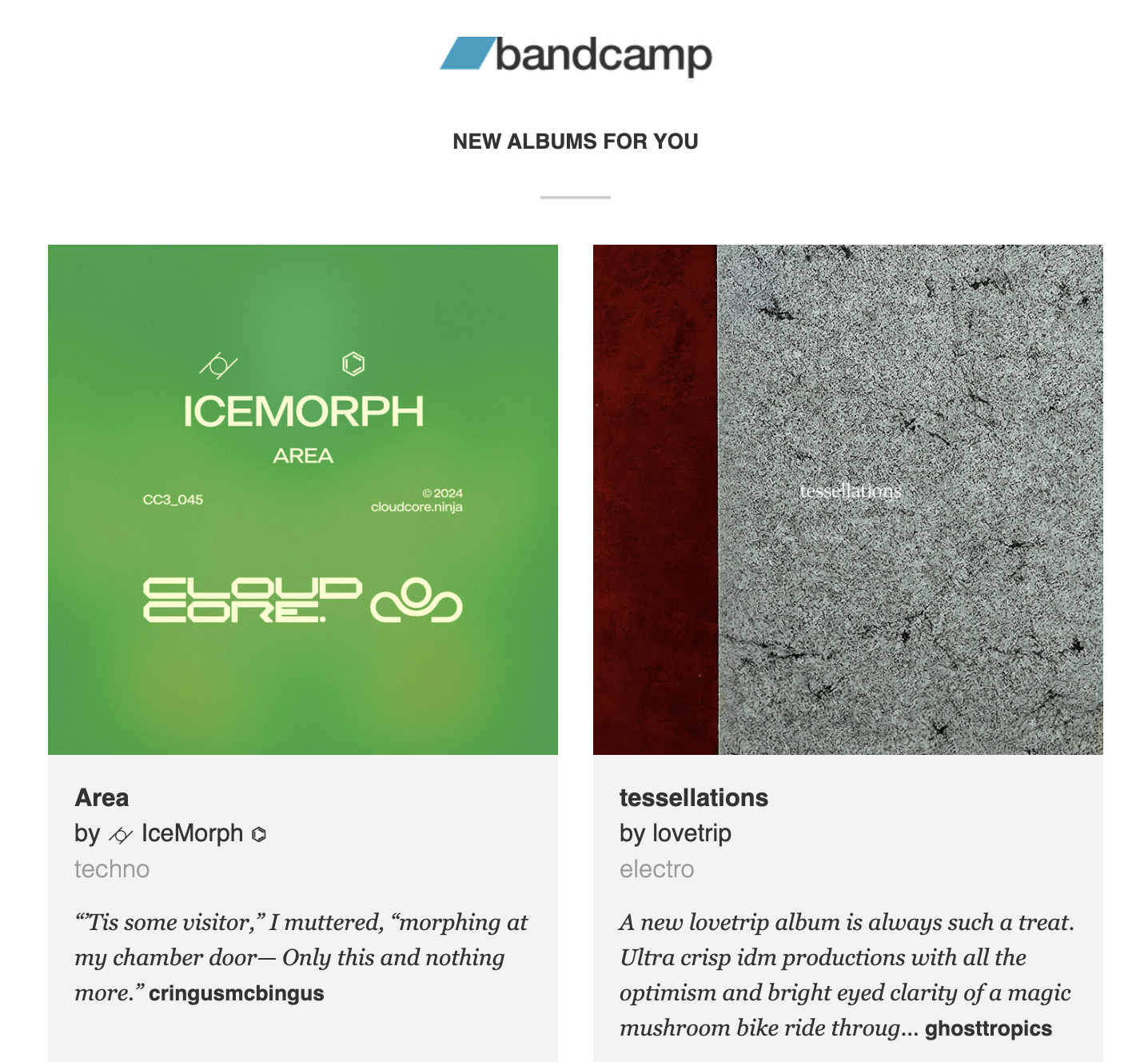

Discovering music through Bandcamp, in contrast to Spotify, feels more community oriented. Aside from the occasional algorithmically driven recommendation sent to my email, the site is entirely focused on a more self-driven exploratory approach.

When I listen to a track on Bandcamp, I can see the supporters of the track, any recommendations that they’ve made about their favorite tracks, and earlier releases from the same artist or record label. That’s another component of it too — independent record labels selling their catalog on Bandcamp, meaning that And one that I haven’t had available since I was picking up sampler CDs at Warped Tour booths as a teenager is now a common and simple conduit for discovering new artists.

As a result, I end up discovering new music by digging into the back catalog of various artists, and more importantly, the record label publishing their music. Following a label to discover new music is a lot like following a promoter (instead of a venue) to discover new music. The label is going to release music that fits together, and a promoter is likely going to book more of the same music you like (or don’t know yet, but you will like) to play at a club. If you go straight to the source, the discoveries are a bit easier.

So there are more pathways to follow, ones that aren’t intercepted by algorithms at every turn, and I also build a closer connection with the artists and record labels I purchase music from. I get an email every time an artist or label that I follow releases new music.

Instead of hoping a new release shows up on my Release Radar playlist, or visiting a record store in person to find out about new music, I get a message in my inbox alerting me to the news. If an artist wants to announce a special show, some new merch, share a discount, or something else, they can also send a message directly to the list of supporters that Bandcamp has built:

It isn’t a personal message (it’s not written just for me—I already had a ticket!), but I nevertheless feel like I’m part of a network of fans, knowing and supporting an artist, instead of an enumerated follower or percentage-based fan on a data-driven dashboard somewhere.

This established community feel, where I can follow an artist (by letting them email me) rather than hoping that I find out about a new track because Spotify’s algorithm happened to add it to my Release Radar playlist that week, feels rooted in community and patronage, rather than a more passive feeling.

I don’t only listen to music that I buy, and trawling through Bandcamp isn’t the only way that I discover music. Some things haven’t changed — DJ sets are still a crucial part of my music discovery pipeline.

Music discovery from a live DJ set #

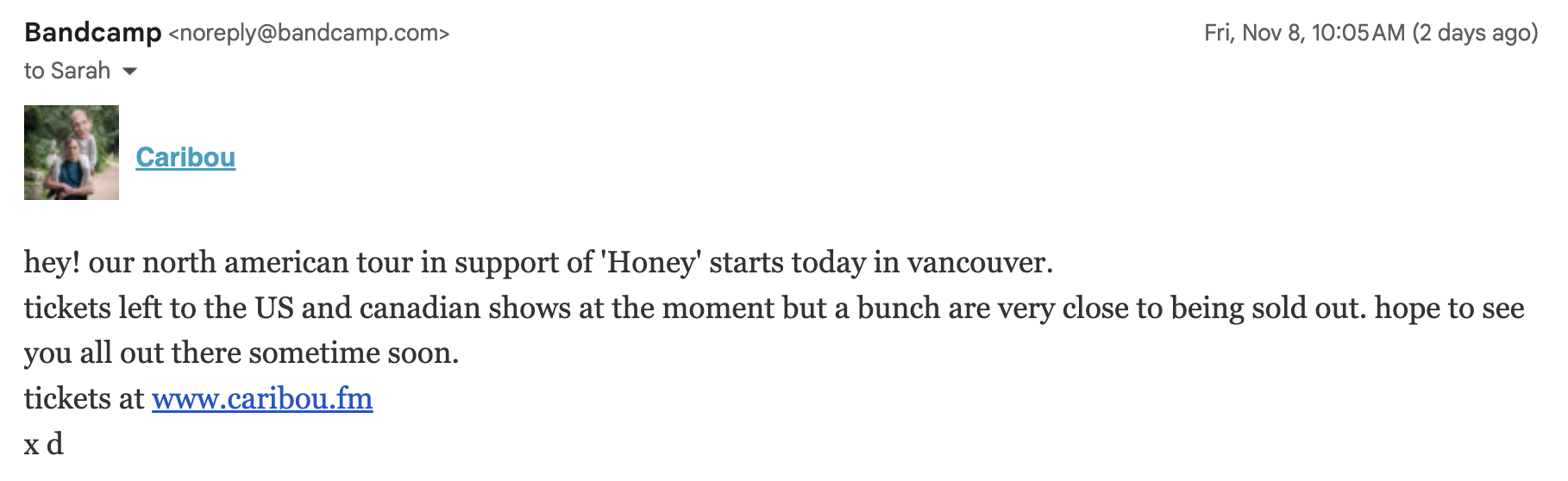

When I go to a DJ set in person, I am the queen of To be less intrusive, I keep my phone on dark mode and sometimes also grayscale. . If I hear a song that I really like but don’t recognize, I’ll pull out my phone and Shazam it.

If Shazam doesn’t work, either due to lack of service or general inability to match the audio fingerprint in the database, I’ll take a 15 second or longer video (often of my feet) and keep dancing, saving the ID for later.

After the DJ set, I’ll go through the Shazams and build out a playlist, usually on Spotify, of the setlist. If I took any videos, I’ll also listen back and Shazam those in isolation to see if I can identify those tracks.

If I’m desperate to ID a song in a video, I’m in a Facebook group dedicated to identifying unknown tracks, or I can post in a discord of friends who are DJs to see if they have any leads, but it usually doesn’t come to that.

After I have a playlist, I’ll listen to it to validate whether or not the identified tracks are actually accurate. Shazam is a fallible tool, and oftentimes it identifies a particularly bassy track as something generic, or picks up an unreleased track as another song (because it has no audio fingerprint for the unreleased track yet). A giveaway is if you Shazam the same song multiple times and get different results every time.

In 2019 I wrote in my music newsletter about a notable Shazam mix-up, where it misidentified a Catching Flies song:

Shazam at one point picked up one of his tracks as “G#/Ab Pad by Drone Pads”, which despite being on Spotify, is pretty clearly stock sounds that could be purchased or that come with a set of pads, like Ableton Push. Artists can use these default sounds live to keep a set flowing continuously, or use software to enhance a performance in other ways.

Shazam falls down most easily when it tries to identify unreleased tracks and finds tracks with some of the same qualities yet are dramatically different. Some other examples:

- Picking up Good Stuff Piano - Original Mix by Syap during a Disclosure set.

- Sonata for two pianos KV448 in D Major, Andante performed by Alfred Brendel (written by Mozart) and C Pad by Drone Pads during a Jacques Greene set

After I test out the playlist, if I really like a song, or if I notice an artist in the list multiple times that I don’t know, I’ll go to their Spotify page and add the top 5 most popular songs, and sometimes also several of their most recent tracks, to a new playlist to dig deeper into the rest of the artist’s music.

At this point, I try to give the tracks some “burn in” time and listen to the playlist in the background a few times while doing something else. If any of the tracks catch my interest in that context, I’ll buy them on Bandcamp or wherever they’re available digitally, if anywhere.

Music discovery from a recorded set #

I listen to a lot more recorded sets than live sets, for obvious reasons. I’ve been finding DJ sets to be a weird sort of pomodoro timer for me when I’m doing focus work, helping me sit down and stay focused by not having to curate a playlist to distract the loud parts of my brain (I’ve always been a person that focuses better with music on instead of silence) while also giving me checkpoints to take breaks, or to force myself to keep working for just a little bit longer.

This focus work approach is perhaps antithetical to the purpose of a DJ set, but it also means that I get to listen to a lot more DJ sets than I might otherwise, and therefore organically discover a lot more music than I might otherwise. A DJ set is curated, and the ratio of familiar songs to unfamiliar songs isn’t calibrated at all like a recommendation-based algorithmic radio station might be. Instead, it is designed to flow and build and react and drive emotion and dancing.

I listen to sets on either YouTube or SoundCloud, and on both sites I keep running playlists of sets to listen to and favorite sets. And here, once again, the community reigns supreme.

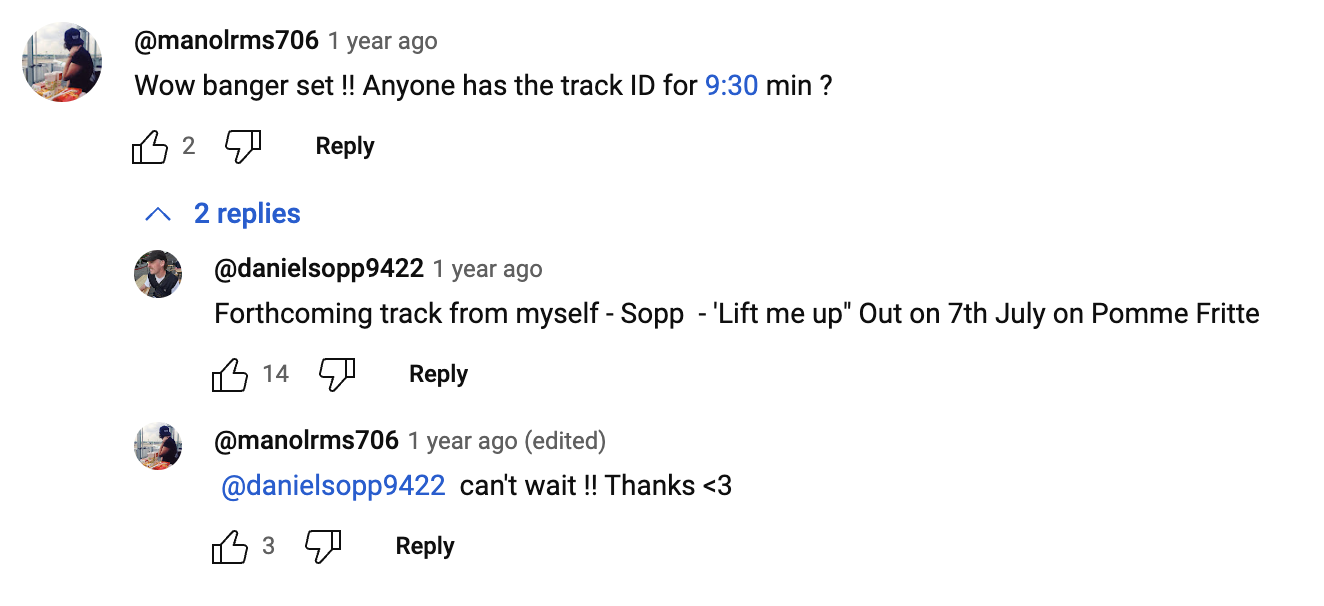

The best way to discover tracks in a recorded set is to read the comments. Sure, you’re not supposed to read the comments online, but the comments on YouTube videos of DJ sets are clutch. There’s MixMag profiled one such commenter, DJ Bigos, a few years ago. that has a full timestamped tracklist, compiled with the help of other commenters.

If I’m listening to a set on SoundCloud, occasionally the artist themselves will have posted a tracklist, but more often I’m relying on Shazam or sorting the comments by timestamp (which I recently discovered was possible!) to find comments around the time the song played and see if anyone has asked for the ID or posted the track ID already.

As a last resort, I can always put Shazam up to my headphone cans to get the ID. This is often a last resort for tracks that haven’t been ID’ed in the comments already, but it can pay off if the track is already released. Otherwise, I’m stuck This is what I did with a track in an I.Jordan Boiler Room set many months ago, where the producer himself replied to a comment asking for an ID with the name and release date of the track. , if there is one, and following up later.

After I have some track names to work with, I can dig deeper. I don’t usually make a playlist (why bother, if I can keep listening to the exact set itself) and instead go straight to Bandcamp or other sites to find the exact track that was played, or other recent tracks by the artist if the specific ID isn’t out yet.

I’ll still listen to the track to verify it sounds the same, that I still like it, and that it hits just as well outside the context of the set. If I don’t do this step very well, I can end up acquiring songs like The Birds by Question Mark, where every time it comes up on a playlist I wonder why I have the song… and then eventually it gets to the part that I liked a lot in a DJ set, and I relax into the track. But it’s almost 6 minutes long! Some tracks are built for mixing, not idle listening.

If I have enough time or like the artist enough based on the one track, I’ll click into their discography and dig into what else they’ve released. I did this with the artist TC4, who I heard at a Sammy Virji set in February (and the song isn’t available to stream in the USA and even the digital copies are sold out), but I dug deeper into their discography and fell in love with a few other tracks, and they ended up having a sale on their digital discography so I got the whole lot.

If there’s a lot of releases, I’ll pick a few newer releases to listen to, as well as some older ones, often based on the track name, cover art, or whatever strikes my fancy at the time.

I’ll listen through them and any that I especially enjoy I purchase and add to my phone to listen to while I commute.

Music discovery through online communities #

I also discover music from friends and folks in online communities. Whether it’s the #music channel in my work slack, a text message from a friend who is really digging a new album, or the chaotically active channels of the Cloudcore Discord, recommendations from people are always a great way to discover music.

In some of these communities, I don’t know basically anyone personally, but we’ve been brought together by other shared interests — purchased music from the same record label, subscribe to the same email newsletter, or got to know the same DJ set promoters. The value here is in the diversity of the loose ties. The further afield the network, the less likely it is that I’ve heard the music they’re recommending.

If I’m lucky, some of them might even host a regular radio show that pipes those song recommendations directly into my ears (shoutout DJ sam3k and NO CHILL).

The flow of my music discovery pipeline #

Because most of my music discovery ends with buying a track, EP, or LP on Bandcamp, I keep the pipeline going by following nearly every artist or record label that I purchase from, so I can add any new releases to my discovery pipeline.

While the volume of messages sent from Bandcamp can pile up and become overwhelming, it’s worth it to discover that an emerging favorite artist has released a new track, or an old favorite has put out an album without me noticing.

I do have to become my own personal algorithm, processing the information in each email with how I’m feeling at that moment (do I really want to listen to another deep house track right now? do I have the energy to discover if this new breaks and hard house artist is going to vibe for me or just stress me out?) to muddle through new discoveries.

My discovery habits are less driven by streaming services, but the platforms are still part of the pipeline.

Of the streaming services I use, the one that makes it easiest to discover music is SoundCloud, with their support of DJs posting sets and bootlegs, radio stations uploading mixes (thanks Rinse FM and The Lot Radio), and record labels often maintaining profiles on the site as well. Because you can repost tracks, you can easily explore from one artist’s profile to another to discover new-to-you tracks. There are algorithmically built playlists like Weekly Wave, but it’s also easy to dig deep into a rabbithole of new music.

I do still use streaming services to help others discover music by sharing links or making playlists.

A while back, I wished for better ways to share music with others:

Though so much of the web revolves around sharing now, it’s still a challenge to share music with others. Mixtapes and mix CDs are a thing of the past, and sending songs back and forth on Spotify is the closest you usually get to sharing your music taste with others.

Spotify deprecated in-app messaging in 2017, recognizing that letting folks use social media for sharing links was the future. Unfortunately, the availability and usage of universal sharing links is still pretty lacking, so you often end up with folks sharing Apple Music links with folks that only use Spotify sharing links with folks that only use Tidal sharing links with folks who primarily listen to tracks on YouTube sharing links with folks who prefer SoundCloud and so on. All the streaming services want you to share their music, but they’d prefer it to happen within their walled garden.

In 2019, I was still enamored of the collaborative potential of Spotify:

A primary reason for the success of Spotify for my listening habits is the social and collaborative nature of it. It’s easy to share tracks with others, make a playlist for a DJ set that I went to to share with others, contribute to a weekly collaborative playlist with a community of fellow music-lovers, or to follow playlists created by artists and DJs I love. My local [music] library can give me a lot, but it can’t give me that community interaction.

I don’t feel that way as much anymore. Maybe it was always a reflection of my in person communities, or not-yet-fractured social media groups primarily using Spotify, or just a shift in my own personal priorities as time has passed, but aside from through which I re-discovered how amazing caroline polachek is and which was partly responsible for my deep dive into pop music last year , I don’t get a sense of community or collaboration from Spotify anymore.

Instead, I find community (and discover new music!) in online communities, in person DJ sets, the comments of recorded sets, and appreciating the notes left by other Bandcamp supporters on various releases. Here’s to another five years of evolving music discovery.

![Supported by section for the SWIM album IDs, featuring one user Crook.Taber.Dubois writing WAITED SO LONG FOR THIS!!! MY LIFE IS COMPLETE «33 and listing a favorite track, ID - doanotherthing [04/23]](/images/2025/01/SWIM-IDs-supported.png)